Bot or not: who are the followers of our candidates for president?

We analyzed the profile of the followers of the Brazilian Presidential pre-candidates on Twitter.

How are we going to discuss the 2018 elections? Where will we look for the innovations that will define the political leadership of the country for the next four years? Campaigns and political debates are becoming more and more a part of the Internet and making use of the social networks and the tools they have to offer. With this, one of the questions that raise concerns is the possible use of manipulation tactics to alter the citizens’ perception about the electoral process in the digital environment.

It is not only about fake news — rumors, conspiracy theories or sensationalist articles published as news. During the electoral period, campaigns, their supporters or any agent that seeks to interfere in the process will find new possibilities as our attention is directed to different feeds and personalized content. Even if these tactics have already been explored in Brazil, the 2016 presidential elections in the US have shown us that this story is just beginning. A part of it has to do with the disinformation created by the interference of bots in the public debate, the automation of social network profiles that do not appear as such and that can blur the perceptions of who is taking part in the public debate.

Will that happen in our elections? Are Brazilian politicians being followed by bots? Keeping the first question in mind, we did a research on Twitter about the profile of the followers of the Brazilian Presidential pre-candidates. The main results are gathered in this post and a full research report with details about the methodology can be seen here [in Portuguese].

What are bots?

Robots, or as they are known, bots, are a specific kind of computer program that can accomplish tasks autonomously from algorithms. They are programmed to run a series of functions, from facilitating web browsing to interacting with people. Even though they are known for supposedly being used to influence the 2016 US elections, they are actually quite common on the Internet and they are essential to its functioning. Of all Internet traffic, 65.1% is operated through bots [1]. Crawlers, for instance, are bots that navigate websites and organize information for search engines like Google, while chatbots can be used in different platforms to answer users, provide information, and make customer service easier.

More specifically on the social networks, bots can be used not only in chats but also to automate accounts and profiles. These accounts can make it clear to the user that they are controlled by bots and be used to promote users’ political engaging, provide information of public interest or even for entertainment. Fátima, a bot created by the Brazilian fact-checking agency Aos Fatos is on Facebook and Twitter and was created to spread fact-checking information on these platforms, for instance. Additionally, on Twitter, we have accounts like @big_ben_clock, which informs the hours like bell tolls, and Ruibarbot created by the Brazilian juridical news agency Jota to provide information about delays on judiciary processes. These profiles present themselves as automated users and do tasks that can have a positive impact on users.

Bots, political debate, and platform policies

However, a problem appears when bots are used to automate fake accounts and profiles, in a non-transparent way so that they appear as regular users on social networks. With the goal to boost individuals and contents artificially, they can be programmed to follow people, interact in discussions or publish and like contents in an orchestrated manner. In the context of political and electoral disputes, bots can be used like this to distort the dimension of political movements, manipulate and radicalize discussions, and create fake perceptions over disputes and consensus on the networks. They can make a determinate figure seem more popular than they actually are or even be used to reproduce discourses in series, making it look like there is a lot of support to a cause when there actually is not.

In Brazil, it is possible to diagnose the use of bots in electoral contexts since at least 2011 and there is evidence that they have been used in Twitter to support candidates in the 2014 elections, during President Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment process, and in the 2016 municipal elections [2].

As these mechanisms artificially boost audiences, they oppose the platforms’ own policies. In Twitter’s case, the platform announced changes in their policy with the goal to fight these automated profiles [3]. These changes diminished the capacities of someone or a service that controls several accounts of spamming through similar tweets or mass likes and retweets.

With this year’s presidential election approaching, concerns about the possible use of these automated mechanisms in disinformation processes and the manipulation of opinions appear. In 2018, for the first time, the Brazilian electoral legislation will allow political advertising on the Internet through the boosting of posts. This election will probably be the first one in history in which the Internet, and especially the social networks, will have an important role in the campaign.

It was exactly before this scenario that we asked ourselves if the current presidential pre-candidates were being followed by bots. Using Twitter’s and Botometer‘s APIs [4], we collected information on a sample of their total followers, analyzed the probability of these followers being bots and made statistical and topographic studies about how the set of followers of each pre-candidate is comprised.

Botometer: cues on whether a profile is or is not a bot

In order to analyze how many probable bots are following each pre-candidate, we used the Botometer to calculate the probability of a Twitter profile being a bot. As we did not find similar tools for other social networks, the research was restricted to the pre-candidates profiles on Twitter.

The Botometer is a system developed by the University of Indiana which uses the random forest algorithm to classify Twitter profiles based on the probability of their automation. This algorithm was trained from databases made by human-identified bots. The tool has a low probability of wrongly classifying profiles which would clearly be pointed-out as bots or real users. The cases that can lead to mistakes by the system are mainly related to dubious profiles, in which bot or human characteristics are not clear. Still, the Botometer showed an average confidence-factor of 86% [5].

Among the diverse results provided by the Botometer‘s analysis of a profile, for this research we used CAP, a percentage index that indicates the probability of an account being completely automated. CAP has already been used in researches that analyzed the behavior of automated Twitter accounts [6] and it is the index recommended by Botometer‘s developers, as it is a more conservative estimate, which decreases the chances of an account being wrongly classified as a bot.

Who are the pre-candidates’ followers?

In order to analyze the profile of the pre-candidates followers on Twitter, we developed a simple method that gathered data collected on Twitter and analyses made in the Botometer, which allowed us to calculate the CAP (that is, the percentage index that indicates the probability of an account being completely automated) of a random sample of the followers of each of these profiles (more details on our methodology can be found in our full report).

The data collection was made between June 4th-28th of this year and the following pre-candidates to the presidency had their followers analyzed: Adilson Barroso (PATRIOTA), Álvaro Dias (PODEMOS), Ciro Gomes (PDT), Fernando Collor (PTC), Flávio Rocha (PRB), Geraldo Alckmin (PSDB), Guilherme Boulos (PSOL), Henrique Meirelles (MDB), Jair Bolsonaro (PSL), Jaques Wagner (PT), João Amoêdo (NOVO), Lula (PT), Manuela D’Ávila (PCdoB), Marina Silva (REDE), Paulo Rabello (PSC), Rodrigo Maia (DEM).

In addition to the pre-candidates, we also included in the research data that was collected from chef Michael Symon’s profile. At the beginning of the year, the New York Times published an article about the bot market, used to increase someone’s following. Michael Symon was identified as one celebrity that used this tactic and admitted to having bought bots. With the previous information that he effectively has bot followers, his data was added to the research for comparison and validation purposes regarding our methodology.

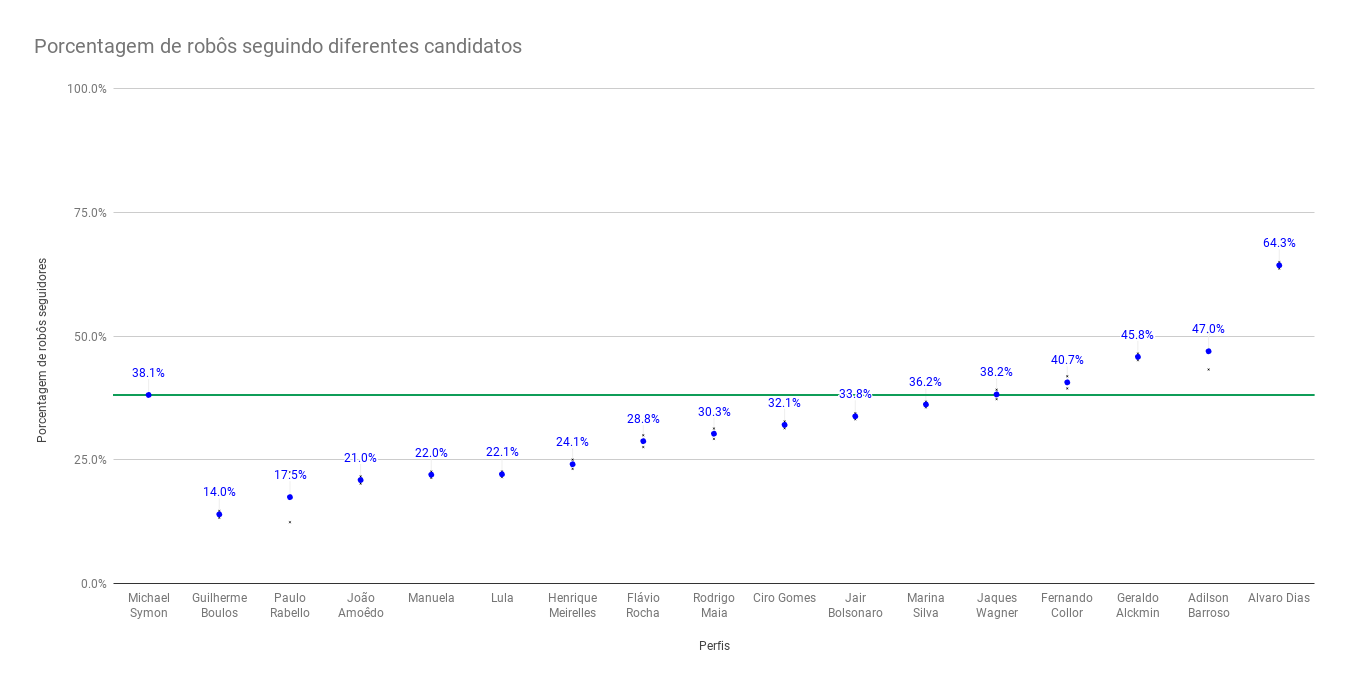

From the Botometer‘s data, we statistically calculated the maximum and the minimum amount of bots that follow each pre-candidate, this is called the Confidence Interval. With the average scores of this Interval, we estimated the percentage of followers of each candidate that are potentially bots, and we organized this data in the graph below:

Pre-candidate Guilherme Boulos showed the smallest percentage, with a Confidence Interval between 13.3% and 14.7%, which represents an average of approximately 9.185 bots among his followers. On the other end of the graph, over Michael Symon’s score of 38.1%, we have Fernando Collor, Geraldo Alckmin, Adilson Barroso and Álvaro Dias. The last one having the biggest percentage of all, with a Confidence Interval of 63.7% and 65.0%, the equivalent to an average of 262.950 bots among his followers.

The percentage did not reach zero or close to zero in any case. This high quantity of bots on the pre-candidates’ profiles, however, does not necessarily indicate that there has been any sort of follower purchase by them or by the marketing companies that support them. Brazil is one of the countries with the largest use of bots on social networks [7] and, according to Symantec’s 2016 report, Brazil holds the 8th largest amount of bots in the world. Moreover, as we have indicated above, this is not something fundamentally new, after all, bot activity on Twitter has been identified on the last presidential campaign in 2014, during the impeachment process, and in the 2016 municipal elections [8]. As these studies have shown, discovering the purpose and the possible controllers of these profiles demands a greater investigation.

Do the bot followers of a pre-candidate also follow their possible opponents?

The ways in which bots act on a platform are very diverse, they are not always the object of purchases, being able to follow users and interact with contents based on key-words, subject, set of interests etc. Mapping these bots starting with who they follow in common can lead to cues about this. There are more chances of bots being activated by key-words, for instance, if they follow more than one profile with similar characteristics.

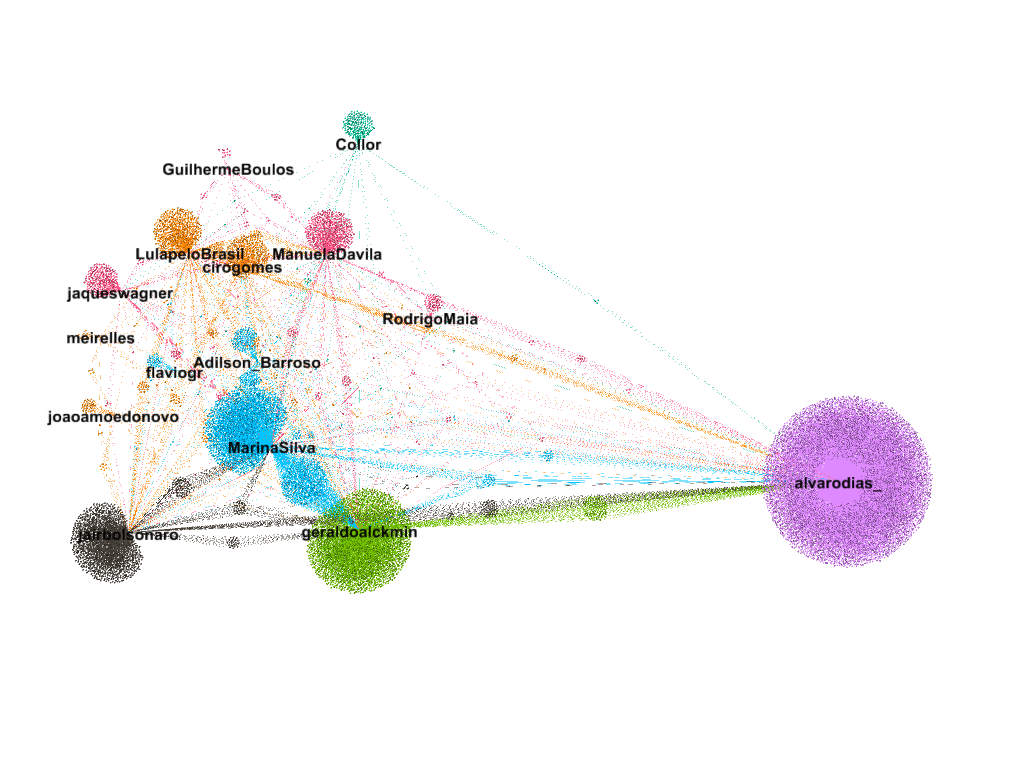

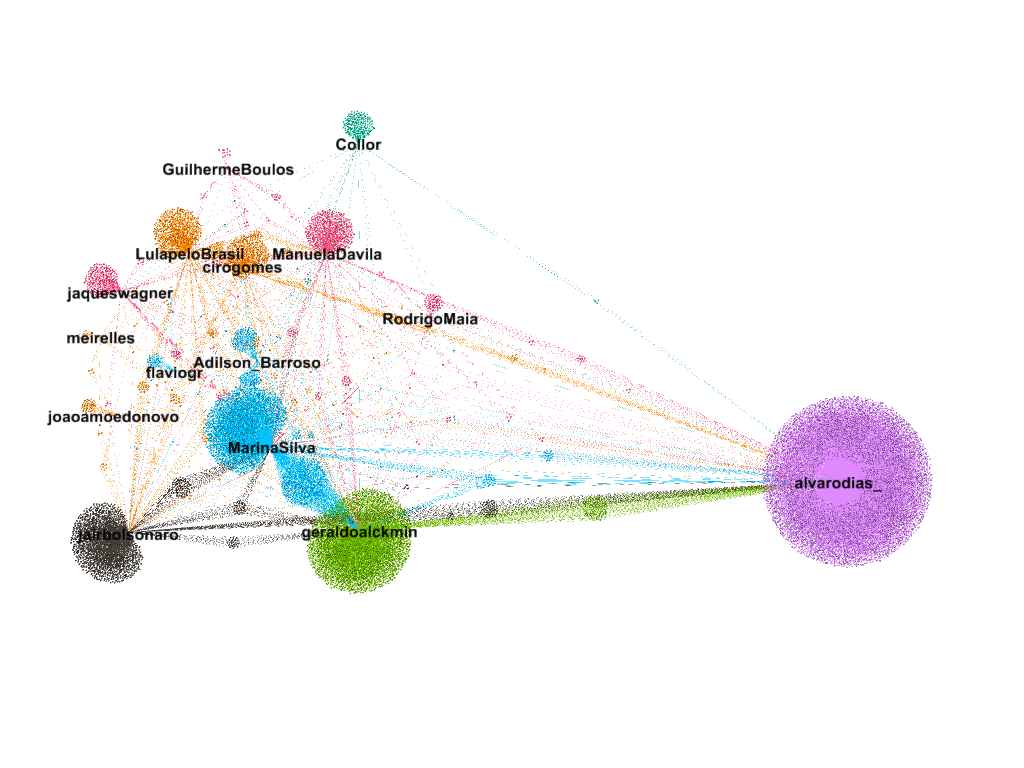

Faced with this and using the same method as before, we mapped the network of bot followers that exists between the pre-candidates. From it, we created a chart representing which profiles followers with a CAP score of over 90% [9] out of this sample followed, with the purpose of checking if these bots followed various pre-candidates in common or only one profile among them. In this representation, the more a pre-candidate is close to another, the bigger their amount of bots in common. The colors indicate the formation of clusters due to a relatively high number of followers shared between them, as it can be seen below:

In the chart above, the clusters which are identified from common followers somehow contemplate the current political and electoral scenario in Brazil, as it is not so far from what has been seen in researches that used a similar methodology to map political debates on the social networks [10]. Also, this kind of approach was already used in other studies to identify profiles that are potentially bots [11], however, they used hashtags and not specific profiles as the basis for collecting data.

Nonetheless, a distortion can be seen regarding the pre-candidate Álvaro Dias, who is clearly isolated from the others. This finding mainly indicates that there is a small number of shared bots between him and the other pre-candidates when compared with the situation of the rest. As Dias presented both a high amount of estimated bots in his profile and a different following pattern from other pre-candidates, we raised concerns that something unusual might have happened in his profile.

Comparisons between bot purchasing patterns

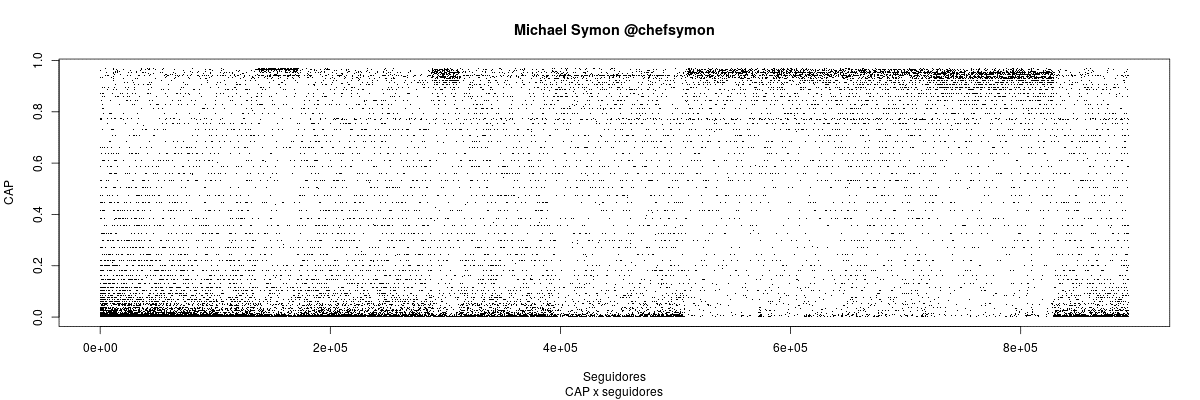

In the aforementioned New York Times article, the methodology that was used allowed them to identify the order in which each account began to follow a profile on Twitter, whether they are or not a bot, and their respective creation dates. This approach enabled the identification of moments in which many probable bots began to follow a profile at once, which could indicate an alleged purchase of bots.

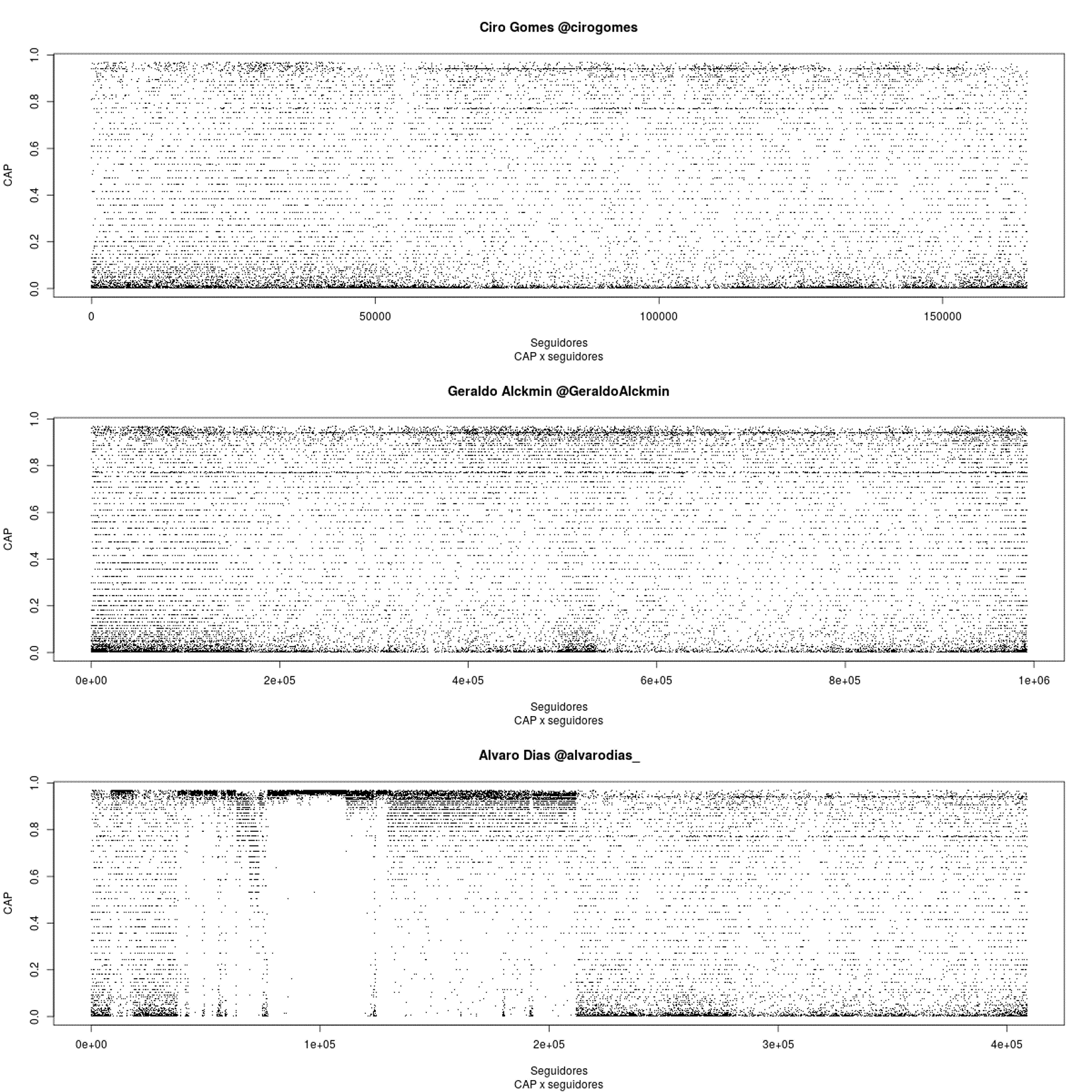

In order to repeat this investigation on the pre-candidates’ profiles, we adapted the methodology to allow for the use of the CAP index calculated by the Botometer. From this, we created graphs crossing the order in which each follower began to follow that pre-candidate (horizontal axis) with the probability of these followers being bots (vertical axis). Concentrations of followers on the top of the graph indicate that many probable bots followed that candidate in a certain moment, while concentrations on the bottom refer to human followers.

First, we used this method in Michael Symon’s profile, as he had already confessed to the purchasing of bots. On the graph below, we see some gatherings and profiles that are likely automated on top (1.0 CAP score), which indicates the moment then those purchases happened.

All pre-candidates went through the same process, and some of the graphs can be seen below:

Out of all analyzed pre-candidates, only Álvaro Dias has shown characteristics similar to the ones seen in Michael Symon’s graph. This abnormal outline, however, does not necessarily mean a purchase of bots but that, at some point in the profile’s history, all new followers were likely to be bots — something that is unusual in an organic growth of relevance.

***

The analyses made by this study do not have the pretention of making categorical assertions about the origin and the use of bots in the Brazilian political and electoral scenario but intend to give a first look to this picture. The conclusions presented here show us that the presence of bots in the political discourse of the 2018 elections will be a reality. Over a million bots follow the pre-candidates and in many cases, more than one at the same time. Furthermore, all candidates have a considerate percentage of followers made by automated accounts. All of this points to the importance that both citizens and the electoral justice are attentive to these matters during the campaign period.

The algorithms used to develop this research are available and can be accessed at https://github.com/internetlab-br/Twitter-Bots

_______

[1] Report: Bot traffic is up to 61.5% of all website traffic. Incapsula, December 9th 2013. Source: https://www.incapsula.com/blog/bot-traffic-report-2013.html

[2] ARNAUD, Dan. Computational propaganda in Brazil: social bots during elections. University of Oxford Working Paper, n.8, 2017. Available at http://blogs.oii.ox.ac.uk/politicalbots/wp-content/uploads/sites/89/2017/06/Comprop-Brazil-1.pdf

[3] https://blog.twitter.com/official/en_us/topics/company/2018/2016-election-update.html https://blog.twitter.com/developer/en_us/topics/tips/2018/automation-and-the-use-of-multiple-accounts.html

[4] APIs (Application Programming Interface) is a set of interfaces established by a software — like Twitter and Botometer — to allow for other applications to use the seftware’s functionalities without having to completely engage with their functioning.

[5] VAROL, Onur; et al. Online Human-Bot Interactions: Detection, Estimation, and Characterization. In: Proceedings of the Eleventh International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 2017, pp. 280–289. Available at https://aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM17/paper/view/15587/14817

[6] POZZANA, Iacopo; FERRARA, Emilio. Measuring bot and human behavioral dynamics. 2018. Available at https://arxiv.org/pdf/1802.04286.pdf; GRAMLICH, John. Q&A: How Pew Research Center identified bots on Twitter. Pew Research Center, 19 abr. 2018. Available at http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/19/qa-how-pew-research-center-identified-bots-on-twitter/

[7] ARNAUD, Dan. Computational propaganda in Brazil: social bots during elections. University of Oxford Working Paper, n.8, 2017. Available at http://blogs.oii.ox.ac.uk/politicalbots/wp-content/uploads/sites/89/2017/06/Comprop-Brazil-1.pdf

[8] ARNAUD, Dan. Computational propaganda in Brazil: social bots during elections. University of Oxford Working Paper, n.8, 2017. Available at http://blogs.oii.ox.ac.uk/politicalbots/wp-content/uploads/sites/89/2017/06/Comprop-Brazil-1.pdf

[9] The CAP score reflects the probability of an account being completely automated. Academic studies selected a score between 40 and 60% in order to consider an account as a bot, however, for this research, we selected a more conservative score with the goal of reducing as far as possible the chances of false positives.

[10] MALINI, Fábio. UM MÉTODO PERSPECTIVISTA DE ANÁLISE DE REDES SOCIAIS: cartografando topologias e temporalidades em rede. In: XXV Encontro Anual da Compós, 2016. Goiânia: Associação Nacional dos Programas de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação. Available at http://www.labic.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/compos_Malini_2016.pdf.

[11] CÔRTES, Thaísa G. et al. O #VemPraRua em dois ciclos: análise e comparação das manifestações no Brasil em 2013 e 2015. In: XXXIX Congresso Brasileiro de Ciências da Comunicação, 2016. São Paulo: Intercom – Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares da Comunicação. Available at http://portalintercom.org.br/anais/nacional2016/resumos/R11-1938-1.pdf

By Lucas Lago (lucas.lago@internetlab.org.br) and Heloisa Massaro (heloisa.massaro@internetlab.org.br). With the support of Francisco Brito Cruz (francisco@internetlab.org.br).

Translation: Ana Luiza Araujo