MonitorA 2022: distinguishing insults from attacks on the content moderation debate

In 2020, we initiated MonitorA – Observatory for political violence, a partnership of InternetLab and AzMina Magazine. At that time, our goal was to understand how political violence targeted women who were candidates for institutional politics. In other words, we wanted to concretely understand how violent speeches gained space on Twitter, Youtube and Instagram.

The research findings corroborated the views of other specialists: women candidates are not necessarily criticized for their accomplishments and actions, but for what they were supposed to be or to do – an expectation related to gender role specificities. Facing this, in that year we found attacks that reduced women’s intellectual capacity, that morally offended them and that made derogatory comments about their bodies. The results of the 2020 research may be found here.

In 2022, we have continued with MonitorA. This turn, besides the partnership of InternetLab and AzMina Magazine, we also count on the participation of Núcleo de Jornalismo. We will focus on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and YouTube.

The political scenario is not exactly the same, but the social phenomenon of political violence is still a problem to be further understood. The social and legal acknowledgment that political violence impacts the life of women, however, has changed. At this moment, we can count on more engagement of different sectors to mitigate the risks that this phenomenon imposes to women and to historically minorized groups.

One of the new elements we have in the current elections is the Political Violence Act. Adopted in August 2021, it states that “discrimination and unequal treatment due to gender or race” is prohibited in the context of representative political bodies and to the access of public functions. Furthermore, the law states that political party propaganda that depreciates “womanhood” or that stimulates discrimination of gender, color, race or ethnicity will not be allowed. The parties are now also obliged to include in their statutes norms to “prevent, repress and combat political violence against women”.

The Political Violence Act also typifies the acts of harassing, embarrassing, humiliating, persecuting or threatening, by any means, a candidate or holder of an elective position with the aim to prevent or hinder their electoral campaign or the exercise of their office, and provides for sentences of 1 to 4 years of confinement, besides a fine.

It is also important to say that the acts understood as political violence that took place on online spaces are regarded as just as severe as those that happened face-to-face. In this sense, according to the law, the publication of facts known to be untrue, if associated to disregard or discrimination to womanhood or to color, race or ethnicity, may increase the sentence in 1/3 up to the middle of the period. The same may occur if the untruthful fact is published by press, radio, television, internet, social media or if it is broadcast live. Besides that, the sentence may be increased in 1/3 if the crime is committed against a person who is pregnant, over 60 or with disability.

Another important law to be considered in this scenario is the Act of crimes against the democratic State, that also includes “religion” and “national origin” as social markers to be observed when we think about political violence, thus, going beyond the markers of gender, race, color and ethnicity. On the referred law, not only women are mentioned, but any person who is targeted by political violence.

The definitions of both laws were not determining for us to outline the research methodology, but, to some extent, have shed light on what we would consider as an insult or an attack. Assuming that social media are not only spaces in which discrimination and attacks occur, but are also spaces instrumentalized by voters to demand actions from representatives and politicians in general, we explain how we defined this differentiation.

What are we considering an insult?

Insults are characterized by hostile and disrespectful language, but they cannot be considered proper attacks, even though they can be harsher than mere criticism. They are commonly used against candidates, and their wording intensifies the criticism and dissatisfaction expressed by users towards candidates. We believe, however, that they should not be removed from platforms. In other words, although they set up a hostile atmosphere, which must be debated, at the same time they allow voters to demand actions from candidates. Some examples of insults are: “liar”, “thief”, “corrupt”, “hypocrite”, “cynical”, “two-faced”, “suck the government’s tits”, “how shameful”, “shame on you”, etc.

What are we considering an attack?

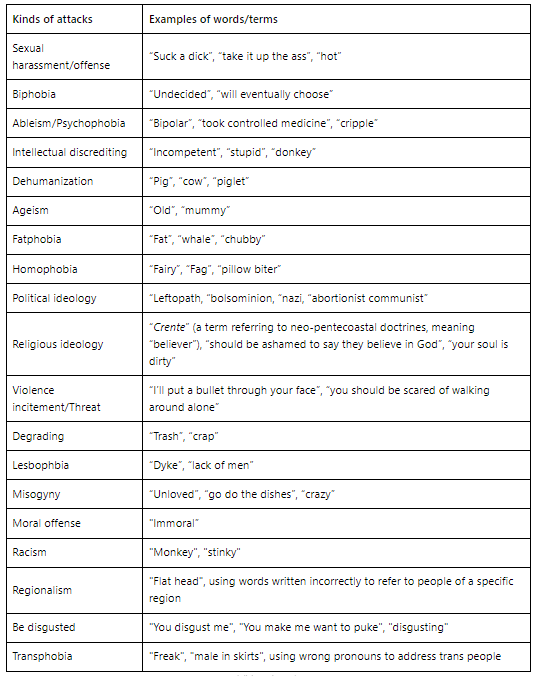

Attacks are characterized by degrading the candidates through the use of specific traits. Frequently, users employ terms that are historically related to attacks targeting historically marginalized groups, as women, blacks, LGBTQIA+ and persons with disabilities. In this case, the discourses aim explicitly at disencouraging candidates to take part on institutional politics, and it is common that they resort to artifices such as dehumanization, sexual offense and harassment, accusations of moral flaws, attacks to political or religious ideology, intellectual discrediting, incitement to physical violence, threats, besides fatphobia, transphobia, lesbophobia, misogyny, homophobia, biphobia and racism.

How are we classifying the attacks?

Can insults have the effect of attacks?

Considering the massive volume that insults might have, it is necessary to take into account the dynamics and speed social media can reach. Because of that, a massively repeated insult leads to a hostile environment and can also result on the candidates’ withdrawing from social media.

Can insults and attacks be mixed?

Although we have differentiated these terms for methodological purposes, it is important to mention that both the categories may appear in association. If, on a tweet or comment on Youtube, Instagram or Facebook, we simultaneously identify an insult and an attack, we will classify both occurrences.

Can different attacks be articulated within a single discourse?

Yes, they can. An example of an overlapping attack may be seen when someone is called an “evandonkey” (evangelic + donkey); here, there is a mix of an attack to religious ideology and a case of dehumanization. On “communist whore”, we find an example of misogyny overlapping an attack to political ideology, since the term “communist” alone would not be considered an attack. When articulated, though, there is a judgment related to “whore”, because there is an association between misogyny and ideological position. The same is true for “disgusting conservative”; “disgusting”, in this case, would be part of the category “be disgusted”, but this category alone would not suffice to understand what is being said, since “conservative” is articulated with “disgust”. It is necessary, thus, to consider the articulations that might emerge from between both kinds of attacks.

What do insults allow us to answer?

Although it is our understanding that insults should not be removed from platforms by moderation policies, we believe that a careful look over this kind of discourse may enable the observation of narratives about the political scenario. Below, there are some questions that we will try to answer throughout the research:

What do insults allow us to respond to?

Even though we understand that insults should not be removed from platforms by moderation policies, we think, on the other hand, that a close look at this type of discourse can allow us to observe narratives that are built about the political landscape. Below are some questions that we will try to answer in the course of the research:

Do women tend to be more insulted than men?

Are black people more frequently called thieves than white people?

Are indigenous people more frequently called lazy than white people?

Is the online environment more hostile to women and politically minorized groups even when we are not dealing with attacks?

How do women candidates feel towards the insults? And towards attacks? Is there a difference between these categories for the targeted candidates?

Do users understand insults and attacks as different levels of severity?

We understand that distinguishing insults and attacks is part of the maturation of the research we have carried out in the last few years. We observe, though, that these classification categories are still under construction and may be altered in case the research leads us to different understandings. Follow the news related to the 2022 edition of MonitorA.