“Fake news”: the polemic reaches the Judiciary

Have you ever wondered how many headlines on your feed you read in a day? How many times have you opened a “bombastic” link sent by a friend or relative and was taken to an article that seemed fake? And when these links go viral and are shared by thousands of people? The topic is hot: after the North-American presidential election, the dissemination of “fake news” — or “rumors” — became the main polemic of the first press conference of president Donald Trump, accused by established news channels of benefiting from rumors during the elections.

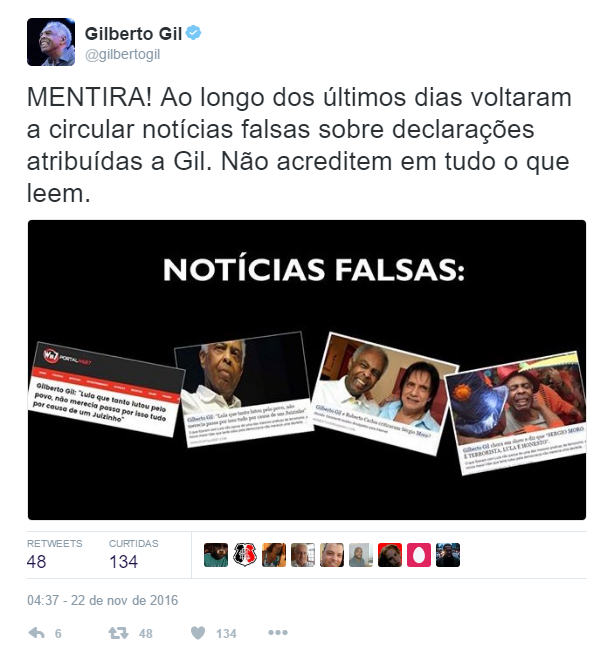

In Brazil, the polarized political environment has also been the stage for rumor cases, which even reached the Judiciary. Last year, singer Gilberto Gil filed a lawsuit against Facebook and the Pensa Brasil website in order to remove a news story that had quotes from an interview that, according to him, never happened. For his lawyers, the website was aiming to create a factoid and use Gil’s name to “attract followers on the Internet and, with that, boost their business”. In the interview, Gil would have defended ex-president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva during accusations made in the Lava-Jato investigation, affirming that “what they did with Lula is one of the biggest terrorist acts, our greatest leader who fought so much for democracy did not deserve such a snub from Judge Sérgio Moro”.

Gil was bothered as phrases he never said were attributed to him, in an article with a truthful look. Pensa Brasil is not a website of knowingly fake news, as Sensacionalista*, so what would point to the reader that it could be an invention?

The first response from the 12th Civil Chamber of the Rio de Janeiro Court of Justice was favorable to Gil, which is why the story is no longer online (only accessible through the “Internet Archive”). In the decision (an injunction), the magister considered the arguments and initial documents enough to give the reason to the ex-minister and determined its removal from the Internet to protect him from “irreparable damages” to his honor and image. But even in Gil’s side, the decision was not enough to prevent the information from being shared on other news websites that were not covered in the request and in comments on social networks and videos. On the other side, the information was considered a “rumor” by Boato.org, a website that checks doubtful content online.

The case is an example of the complexity of this phenomenon. A recent comparative analysis between the engaging of Facebook users generated by rumors, on the one hand, and news produced by renowned newspapers and news channels, on the other, pointed that, in the final stages of the North-American presidential election, the rumors were more popular. The consequences can be serious when it comes to accessing quality information (with reliable sources and checks done), a picture that is worsen if the difficulty of many users in critically judging the quality of the news they encounter is also considered. A study from Stanford University revealed that, in last November, 80% of students in the US could not differentiate normal news from advertising. A 2011 report from the British institute Demos brings even more alarming data, turned to the British reality: around 25% of young people between the ages of 12 to 15 would not check any information seen on the social networks and only ½ of children and adolescents from 9 to 19 would have contact with any discussion in school about the reliability of information found on the Internet.

Last year, communication media and journalists began to pressure Facebook to think what would be its role in face of this reality. What would be the impact of an information that did not go through any editorial filter or checking, but was shared millions of times? In November, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg released a statement saying that there are risks in controlling fake news, but signed to possible changes. On December 15th, Facebook announced the creation of a feature for users to flag if a news article is doubtful, so that the company can take actions to make it less visible. The measure will be first launched in Germany, where chancellor Angela Merkel has shown herself worried with the impacts of sharing rumors on the country’s elections. Indeed, if we consider the reach and the importance of Facebook in the public debate, it is a considerable power.

With the subject in its agenda, how should the Judiciary deal with requests that involve articles or pages that show fake or inaccurate information? Aside from not always having effects — the content removed from one website can show up in another — , the discussion can place the Judiciary in a tricky position. The task of analysing the “veracity” of news published and shared on the Internet is not an easy one, leaving judges to face grey areas: at times, there is no objective criteria to make this kind of assessment and delicate issues, such as protection of sources, will appear. The complexity (and the risk of occurring abuses, like allegations that legitimate contents are fake) could still be aggravated if decisions of removal happen without giving the other party the opportunity to manifest — as it was the case with Gil’s injunction.

Rumors have always been common in society; from pamphlets and social columns to tabloids and speculations about the lives of celebrities. The new challenge is to stop its advances beyond mere snooping, reaching a power of manipulating the public opinion with important political repercussions. Before, to oppose them was a question of honor. Now, it can be a question of citizenship.

*T.N.: a Brazilian kind of Borowitz Report.

Materials

PDF of the commented decision [in Portuguese]

PDF of the Stanford University study; a comparative analysis between “rumors”, mainstream media news and their engaging on Facebook.

By Dennys Antonialli, Francisco Brito Cruz and Mariana Valente

Translation: Ana Luiza Araujo