Black Mirror: “Be Right Back” (S02 E01), mourning and digital heritage

The representation of the self in the digital life

By Artur Rovere Soares and Rafael Viana Ribeiro

Black Mirror‘s dystopias follow the tradition of science fiction anthologies, like the classic The Twilight Zone (1959-1964), and show the best that this genre has to offer: stories and universes that play with technology’s possibilities and limitations and with how we relate to it, confronting us with difficult questions that surpass our own lives, involving themes like death and the human condition. Series like Black Mirror which are set in a not-so-distant future are particularly shocking not so much because of the incredible technologies imagined by its writers, but by their closeness to our current reality.

In Be Right Back, an episode from the series’ second season, the protagonist named Martha loses her boyfriend, Ash, in a car crash. During her mourning period, a friend signs her up — against her will — to a new service offered by an online company: a kind of artificial intelligence that is capable of creating a “digital Ash” with whom Martha could communicate through messages. In short, the algorithm “read” Ash’s posts on social networks like Twitter or Facebook and from there it was able to “recreate” the deceased in a digital version. Before Martha could disagree with the idea, she received an email under Ash’s name saying “it is really me”.

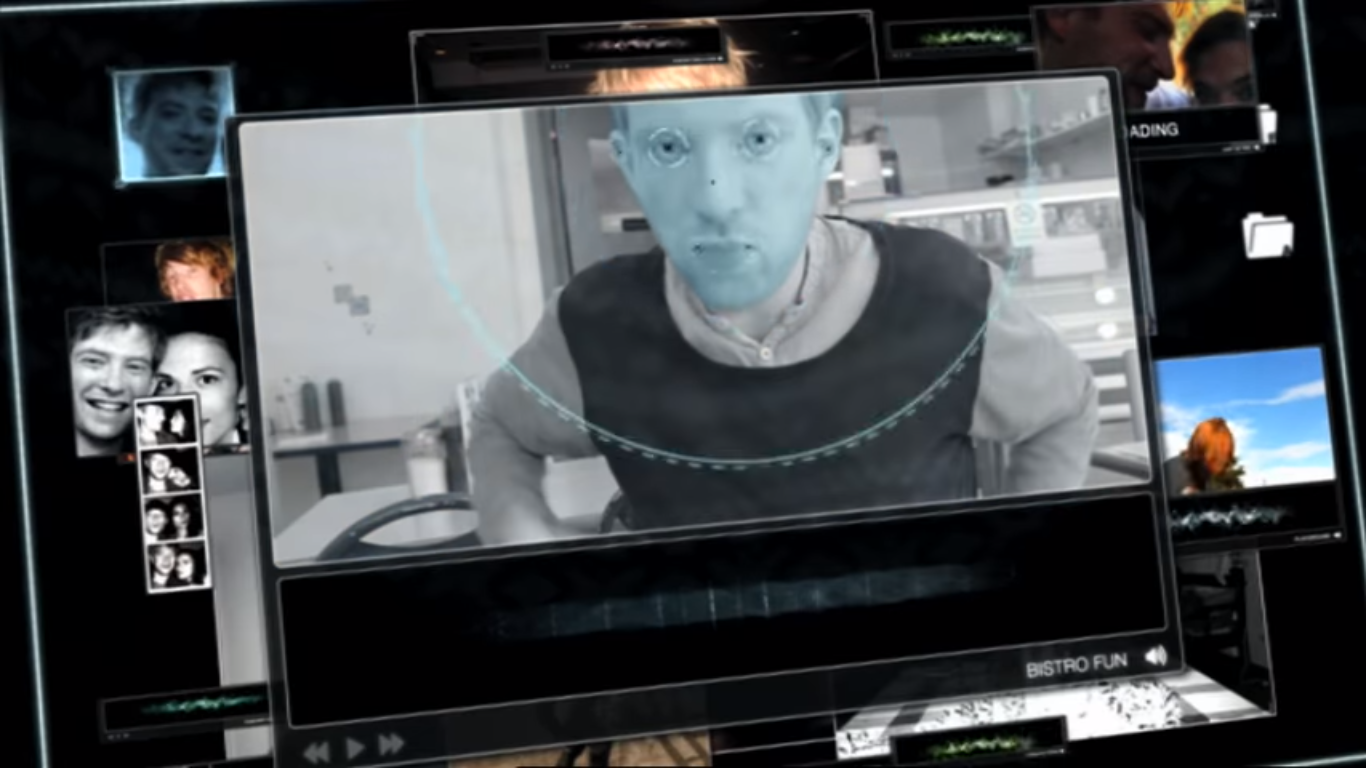

At first, Martha was reluctant to the idea but encouraged by her friend and under the strong pain of grief, the character continues to explore the service, giving more and more data to feed its databank and create a more “faithful” Ash. With photos and videos, the service offers to the widow the possibility of “talking” with a digital reconstruction of Ash’s face. Even today, it is worth mentioning that it is already possible to do things like this: a team of scientists was able to make fake videos of Barack Obama giving a speech, for instance. Eventually, through the artificial intelligence that copies Ash, the company convinces Martha to buy a robot that imitates the body of her deceased boyfriend — a machine which is able to walk, talk, and interact with human beings as if it were one of them, or almost.

Ash’s synthetic copy is not, after all, Ash himself but an android — a robot created to reproduce the human appearance and behavior. And, in spite of its remarkable resemblance to the deceased man, it is the differences between the original and the copy that highlight the fundamental limitations of the latter. Even though some of the differences are linked to the fact that “Ash” is effectively a machine — and therefore does not bleed, breathe, needs to be fed or has its own will –, there are more subtle differences that contribute to its strangeness and makes us think about the idea of a digital representation — and how technology companies relate to it.

The episode’s artificial intelligence was created from Ash’s “digital footprint“, that is, only from what he decided (or was able) to convert into digital information while he was alive — above all, photos, videos, text messages, and posts on social networks. In this way, the databank that fed the artificial intelligence suffered from an inevitable selection bias. In other words, all that Ash decided to (or was not capable of) not convert into data remained outside of his “posthumous memoirs” and thus, off of the “new Ash”. Some are physical characteristics, like a birthmark on his chest that the synthetic body did not recreate as it was not shown in any photograph. Others are more unsettling: in various moments, it is clear that the machine does not have the memories or references brought up by Martha — frequently, of things that happened offline. During a walk, Martha is surprised when the artificial intelligence (AI) asks her to show it the landscape — Ash never saw much in landscapes, after all. By assimilating this newly acquired information, the AI alters its behavior and reacts accordingly, being bored by the view of the hill: “it is just a bunch of green, isn’t it?”. It is in moments like this that it gets clearer that there is not any Ash within the machine, but only its neural networks, which are adaptable and fed initially only with the knowledge of what Ash had shared on the digital means while he was alive — that is, his digital representation.

In the same way, we have our own digital representations — our image which is available on the Internet, including our profiles on social networks, photos, mentions in news articles, but also the whole set of data used by third parties (humans, machines, or institutions) to make decisions that affect our lives. Our “digital self” is frequently everything that is seen to judge our “real self”. From the semi-known crush who will take a look on your photos before a date, to the future employer who may not like your political tweets, the incomplete and many times distorted image that the Internet reveals is used to define who we are to the eyes of others.

Incomplete because these representations are inevitably cutouts of what we are and consume — we do not share every moment of our day, like the good morning when we wake up to the complaints we make at the cafeteria, but these offline moments are as much part of who we are to the people around us — or even more — than our stories on Instagram or the memes we share.

Distorted because even this cutout is not defined as a mere mirror of who we are outside of the Internet, but it is constantly reshaped by our interactions on the digital platforms and by their interests. Who I am to the eyes of Facebook and its users depends not only on what I decide to post but also on what the company Facebook prefers that I share — by controlling the content of our feeds, for example. The company recently began to test changes that make the lives of independent content producers more difficult, that is, those who do not pay it.

At the end of the day, social networks are just companies with the duty of making profits to their shareholders. And companies like Facebook, Google, or Twitter will do everything to explore their main resource, the user data that they collect and process, in the most efficient way possible. This means that economic choices guide their design, code, and structure decisions — the usability ones –, and therefore also influence the kind of content which is produced by their users — and even who their users are. Like in a shopping center, Facebook is not a market square that by chance has stores, but stores that designed the “ideal marketplace” in order to obtain the biggest possible profit over you: even the emoji selection now goes through a consortium including companies like Apple and Netflix. My “digital self” is then the product of my choices as well as the choices of large companies, who often have different interests than my own.

Without us realizing, the way in which we present ourselves and how we are read by the world has radically changed — and with the participation of the data economy in this process, some economic relations which are rarely known by the public began to be determining factors to our affections, jobs, and aspirations. Maybe it is time to think better about the digital representation of ourselves and question if our digital replicas really mirror who we are offline.