Women journalists receive more than double the offenses of male coworkers on Twitter

Polarization and organized and institutionalized attacks to freedom of press boost misogynistic discourse against political journalists

Warning: the following article presents excerpts with explicit misogynistic and racist content. We chose not to censor them, because we understood their importance for exemplifying how violent the debate is on social media, how violence against women is disseminated, which terms are frequently used, and how we can identify it.

Article originally published by AzMina Magazine, by Jamile Santana.

“Bitch. Go spread your legs and fuck Lula”. That was the first message Eliane Cantanhêde, a journalist, columnist of the newspaper Estado de São Paulo and radio commentator of Globonews Em Pauta, Eladorado (SP) and Jornal (PE) stations, received in the morning of November, 18th. The offense arrived in her private inbox on one of her social media professional profiles. This, unfortunately, it’s not the only offensive comment she received on her social media: some of the offenses were left open on the comments to her posts, documenting the misogyny and violence to whomever wants to see them.

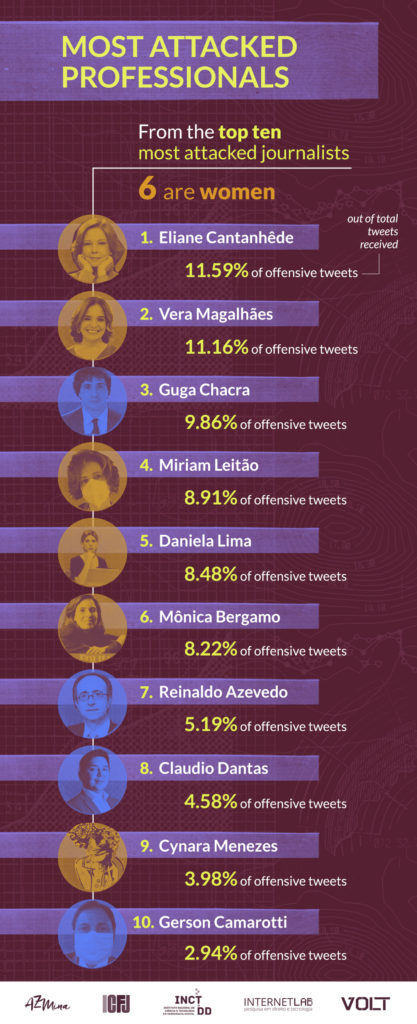

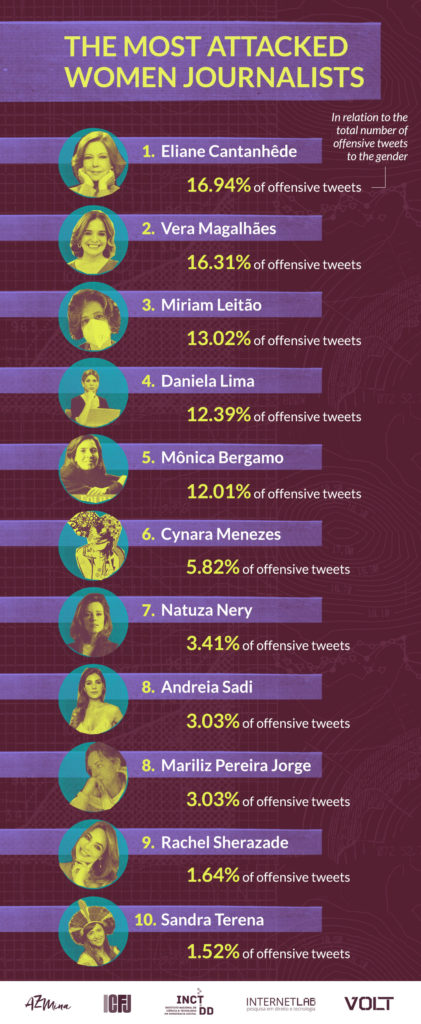

Cantanhêde leads a ranking of impunity and attacks to press professionals in Brazil. When compared to their male coworkers, women journalists receive more than double the offenses on their profiles on Twitter. This was one of the worrisome findings of a data analysis conducted by AzMina Magazine and InternetLab, along with Volt Data Lab and INCT.DD, on the timeline of Twitter. The growing wave of attacks to the Brazilian press also appears on reports by the National Federation of Journalists (Fenaj) and the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (Abraji). Whether on online or offline environments, violence has the female gender as its main target.

The survey carried out on Twitter showed that users who start attacks against journalists attempt to delegitimize women’s intellectual capacity to practice the profession, and to silence the press. They also criticize the journalists’ physical traits in order to divert attention from their journalistic agenda and to spread false information about the professionals.

200 profiles of Brazilian journalists were monitored on the social media. Based on a dictionary composed of offensive, misogynistic, sexist, racist, lesbo, trans and homophobic words, we collected 7,1 million tweets with offensive content on 133 profiles of women journalists, and 67 men profiles. In a more thorough analysis that considered the period from May, 1st to September, 27th, the monitoring identified a group of over 8,3 thousand tweets with five or more engagement actions (retweets and/or likes). They were verified one by one to identify whether the content was a direct attack to the journalist.

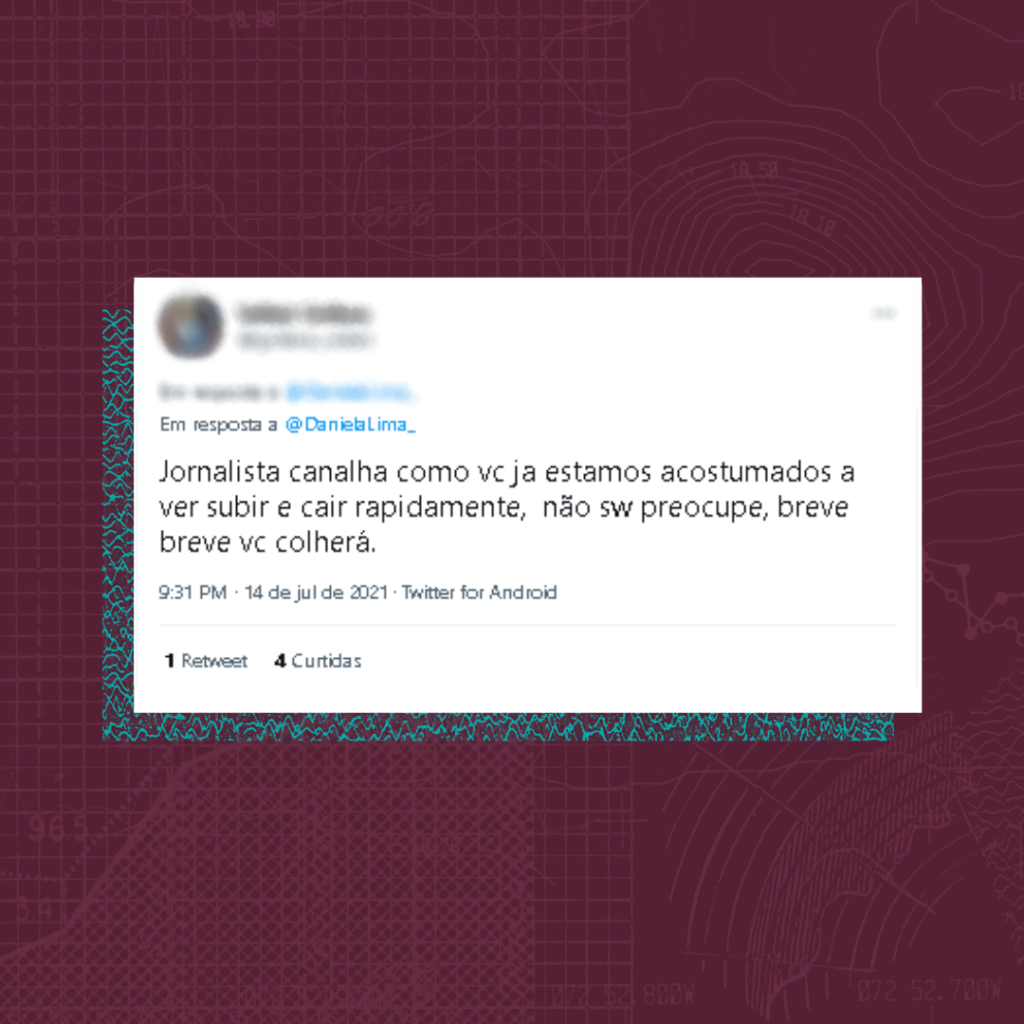

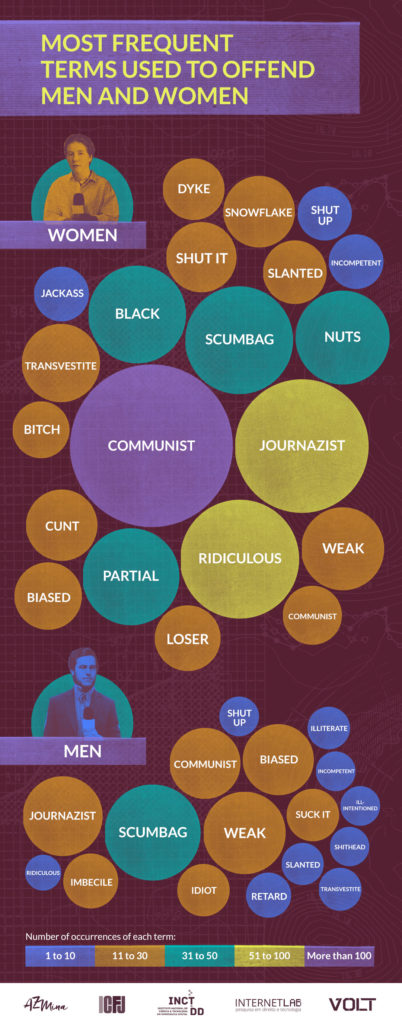

Professionals that cover political affairs are more exposed to massive attacks. While only 8% of the offensive tweets directed to male journalists were in fact hostile, 17% of the tweets directed to women journalists were personal attacks. Among the most frequent terms used against women we find “ridiculous”, “scumbag”, “nuts”, “wuss”. The majority of the aggressions also suggest that women are incapable of interpreting texts or political scenarios.

To men journalists, direct attacks are less frequent and the offenses are often mixed with attacks to other women or to the general press. Many messages targeting men also contained misogynistic comments offending female figures related to them, as mother, sister and coworkers.

According to the anthropologist Fernanda K. Martins, a research coordinator at InternetLab, “misogyny is supported and socially spread throughout movements that target women even when the goal is to attack a man. Aggressions directed to coworkers and women relatives point out to a social behavior that assigns the female gender as naturally targetable, naturally susceptible to discourses that belittle and disregard women”.

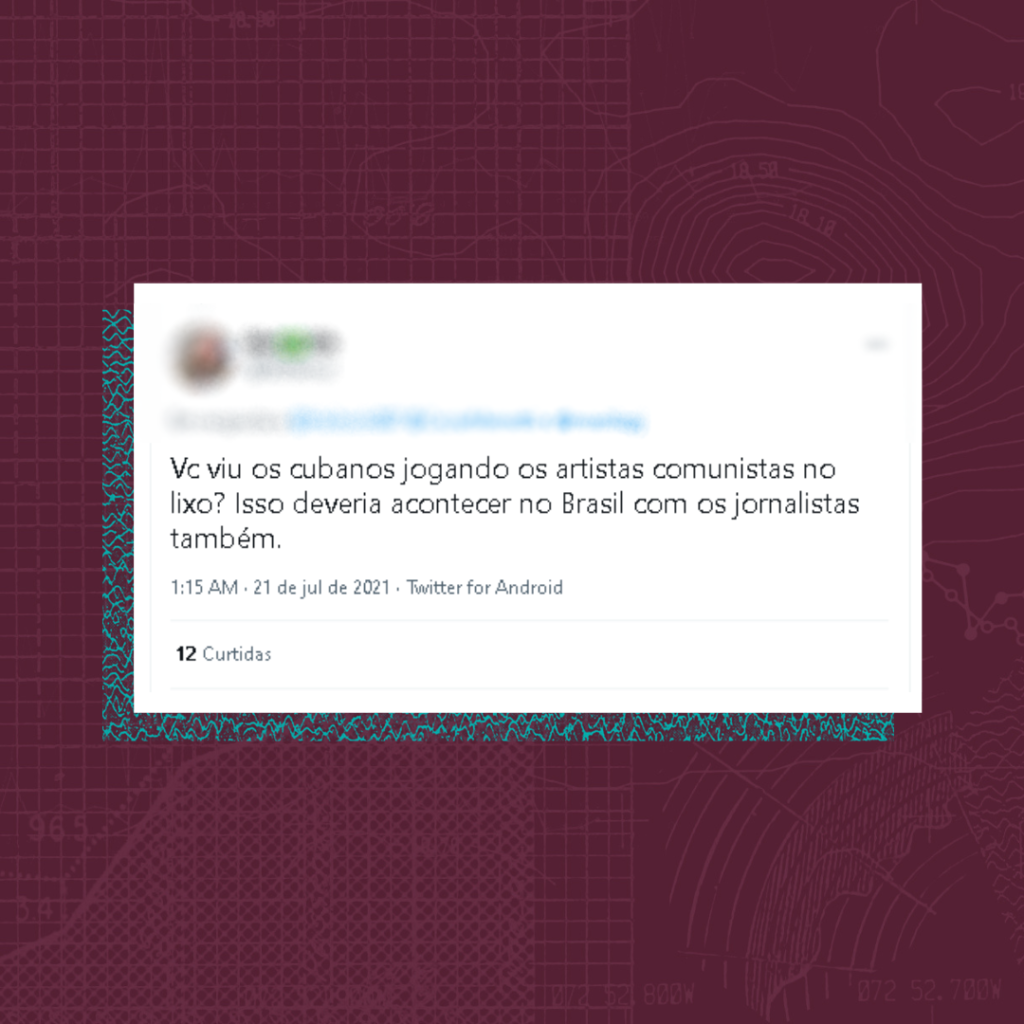

What is found in common to both genders is the use of terms that attempt to place professionals in a specific political spectrum, referring to them as “communists” or “journazists”, besides accusations of their being somehow “partial” on their coverage.

Concerted actions

On the top of the ranking of the most offended journalists are Eliane Cantanhêde, Vera Magalhães (host of the TV show Roda Viva, columnist of O Globo newspaper and commentator of CBN radio station), Daniela Lima (anchor at CNN) and Miriam Leitão (journalist at O Globo newspaper and at TV Globo, Globonews and CBN channels). They shared the opinion that the attacks are even more virulent when initiated or propelled by political figures, as the president Jair Bolsonaro. AzMina magazine has released a video on its YouTube Channel explaining why the president’s aggressions to women journalists are a problem.

Cantanhêde recalls that personal attacks to journalists have started at the time PT (Worker’s Party) was in office, and were done by the party’s supporters. She also recalls having been insistently attacked by PSDB (Brazilian Social Democratic Party). The same newspaper article displeased both parties. “But Bolsonaro not only used this tactics, but also started to disrepute personally the journalists, which stirred his supporters up”, she pondered.

To Magalhães, the attacks are strategic: “I understand they are purposely misogynistic and sexist, precisely as a way of disreputing women journalists”. She believes her case is aggravated by having many times criticized PT, “and I do the same to Bolsonaro”. Currently, though, the coordination of those offenses stems from the president, his family and his ministers, Magalhães affirms. “That didn’t used to happen on previous governments. It’s violent and concerted”.

The journalist Mariliz Pereira Jorge, columnist at Folha de São Paulo newspaper, scriptwriter and anchor at MyNews channel, reports that facing hostility to practice her profession is, unfortunately, a part of her routine. According to Jorge, the problem is that the attacks have become massive and more organized. “When a tweet comes from the very presidency, or from the representatives of the governing coalition, I already know there will be a flood of offenses”. Frequently, besides being offensive, the messages are intimidating.

Besides the swearing, the journalists must fight the dissemination of fake news about their lives and carriers, which is also a political strategy for disreputing those professionals. Miriam Leitão, for instance, is constantly offended with expressions as “bank robber” and “snake woman”, a term coined by the president’s followers to minimize and mock the episode of torture suffered by the journalist during the Brazilian military dictatorship.

“I was in Twitter trending topics because they used a picture of mine saying that it was of my detention for having robbed a bank”, Leitão commented, adding that she has never held a gun and that this information has been refuted dozens of times. “But, every now and then, there is a new wave bringing this back”. She notes that fake profiles create artificial waves of attack that pollute the debate and distort the dialogue.

Gender and race

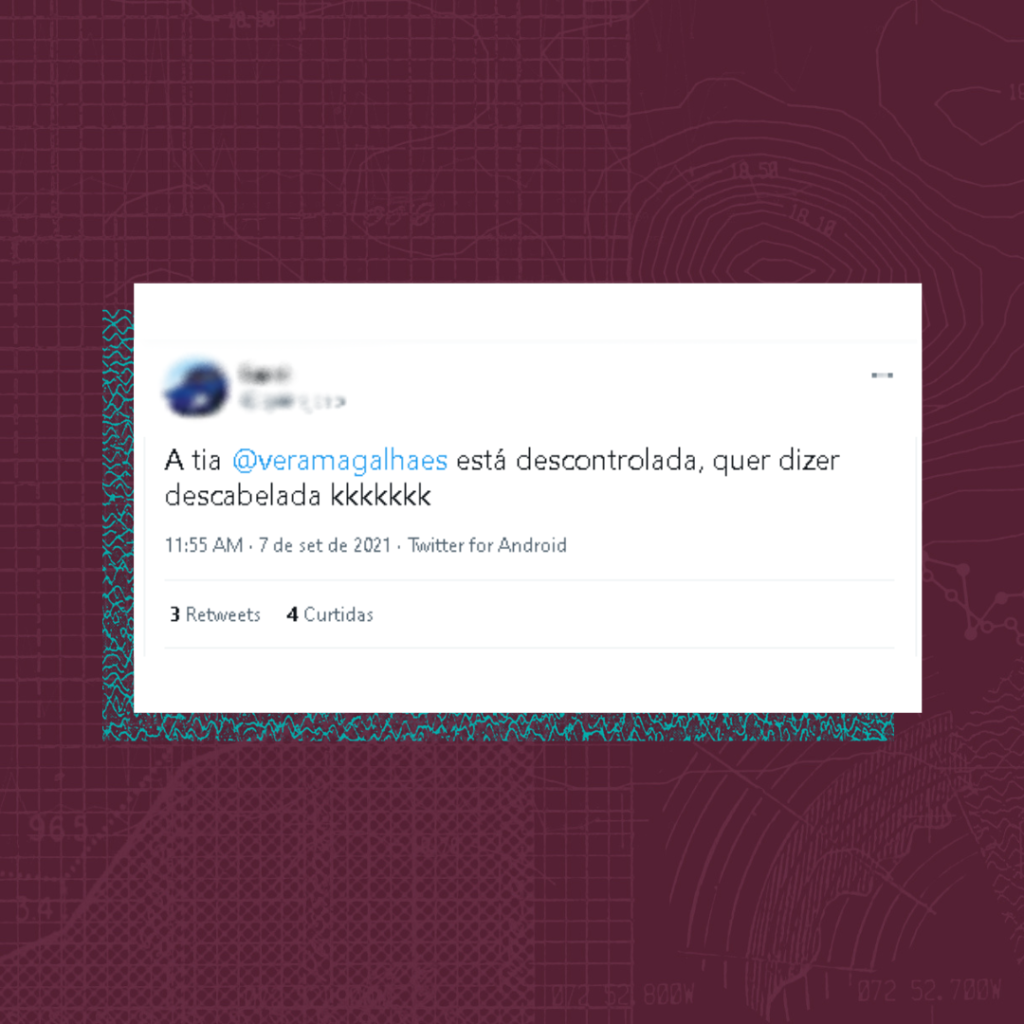

As usual in misogynistic narratives, women also suffer offenses directed to their bodies, their relationships and their ages. Vera Magalhães and Eliane Cantanhêde had their intellectual health put at stake. “They think they offend me, but I never cared for hiding my age. I’m proud of my journey, of being the grandmother I am”, said Cantanhêde.

The professional practice of Magalhães’ husband, who is also a journalist and who has worked as an advisor for different politicians on the national scenario, is frequently discussed on social media as something that supposedly interferes on the career and opinions of his wife. A similar strategy is observed with the journalist Eliane Cantanhêde.

The conclusions of the monitoring are very similar to the ones presented on the report developed by Abraji, which showed an index of 56% of online attacks to women journalists in 2020. The report also showed that swear words, cusses and misogynistic terms were used when the victims were women. “This scenario draws attention to the need of legal and institutional mechanisms for protecting freedom of speech, ones that are specifically attentive to gender issues”, stated Christina Zahar, executive secretary of the association.

Many users imply that black and indigenous women have taken advantage of their characteristics to access the professional positions they achieved. That is the case of the journalists Maju Coutinho, a black woman, and Alice Pataxó, an indigenous woman. “Aren’t you a monarchist? What about the electric power you’re using there, squaw? Back in the empire there was nothing like that”, wrote a user, after the journalist posted an image in which an indigenous person takes a picture with their cell phone.

How to act

Besides the violent experience of opening social media and facing this sort of attack daily, the journalists highlight the difficulty of reporting those contents to the platforms.

Mariliz Pereira Jorge affirms having reported many attacks, but the platforms failed to respond appropriately. The feedback she received informed that the content did not violate the platform policies. “A woman who posts a picture of her breast may be banned because that is much more violating to the platform policies than a threat of rape or murder, as has happened before to me and to other coworkers”. She also ponders that aggressions generate engagement from other users.

To Miriam Leitão, every profile should correspond to a legal person or a company that can be legally identified. She suggests that platforms take responsibility for determining who is real in waves of organized attacks, and for neutralizing and excluding fake profiles, because bots have no face. “When I receive a sexist or an untruthful offense, who can I sue, if I want to?”, she questions.

The monitoring has identified that many tweets with explicit aggressive content, for instance “whore” and “slut”, have already been deleted.

Platforms position

In a note, Twitter informed having a policy against abusive behavior (that deals with attempts to harass, intimidate or silence a person) and a policy against the spread of hate speech (that establishes it is not allowed to promote violence, to attack directly or to threat other people based on specific categories or characteristics). If the violation is confirmed, different corrective measures are taken, which range from deletion or visibility reduction of a tweet, to permanent suspension of an account.

Regarding the great volume of fake profiles identified as authors of offensive tweets, Twitter informed having rules to address attempts, whether by using spam or fake accounts, of manipulating the debate on the platform. These rules determine it is not allowed to use Twitter services with the intent of amplifying or suppressing information artificially, nor to take part in behaviors that manipulate or undermine the experiences of other users. Twitter has been using machine learning and team training to identify those profiles. When there is a suspicion, detected accounts go through the so-called challenge (as confirmation of email or telephone, or typing of a captcha code, for example) to prove there is a person behind the account. If the account does not pass the challenge, it undergoes the applicable corrective measures.

Finally, Twitter informs that the rules and policies are periodically reviewed; among them, there is a policy against hate speech propagation that intends to include further categories in what they call dehumanizing language. The company also affirmed that it counts on a Reliability and Security Council, composed of 40 organizations and specialists in 13 regions, including Brazil.

* The project “Understanding How Influence Operations Across Platforms Are Used To Attack Journalists And Hamper Democracies” is carried out in a partnership of InternetLab, INCT.DD, Instituto Vero, DFR Lab, AzMina and Volt Data Lab. The research is financed by Partnership for Countering Influence Operations, from Carnegie for International Peace, and is also supported by the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ), via Volt. The study aims at understanding the patterns of attacks to journalists in digital environments, with specific focus on issues of gender and race.