SPECIAL | Did you not read the app’s privacy policy?

One of the pillars of the right to the protection of personal data is the obtention of consent. The legal jargon can be complicated, but the idea is simple: if a company wants to undertake any activity with any information about you (that identifies you or can identify you), it needs your authorization.

The Brazilian Internet Civil Rights Framework, for example, secures this precisely: the internet application user has the right to free, express [1] and informed consent to the collection, use, storage and processing of personal data (art. 7º, VII e IX) [2]. Currently, there are also bills being discussed at the National Congress that intend to strengthen this right even more.

It is worth mentioning that although there is the requirement for the consent to be free, express and informed, there is not a word in the law that specifies the method through which this consent should be obtained. Keeping this in mind, we analyzed how the most popular children’s apps in Brazil have been dealing with this legal demand.

Our Findings

1. All analyzed apps have a privacy policy.

All companies behind the consulted apps have put on paper, to some extent (we will see more about this in tomorrow’s post!), the rules of the game, so to speak, about what they do and intend to do with their user’s data — rules to which you should consent. All of them do notify, this is, inform about their privacy policy. This is an important step for any consent to be informed.

2. The methods for obtaining consent are varied; most of them choose a model of implicit consent.

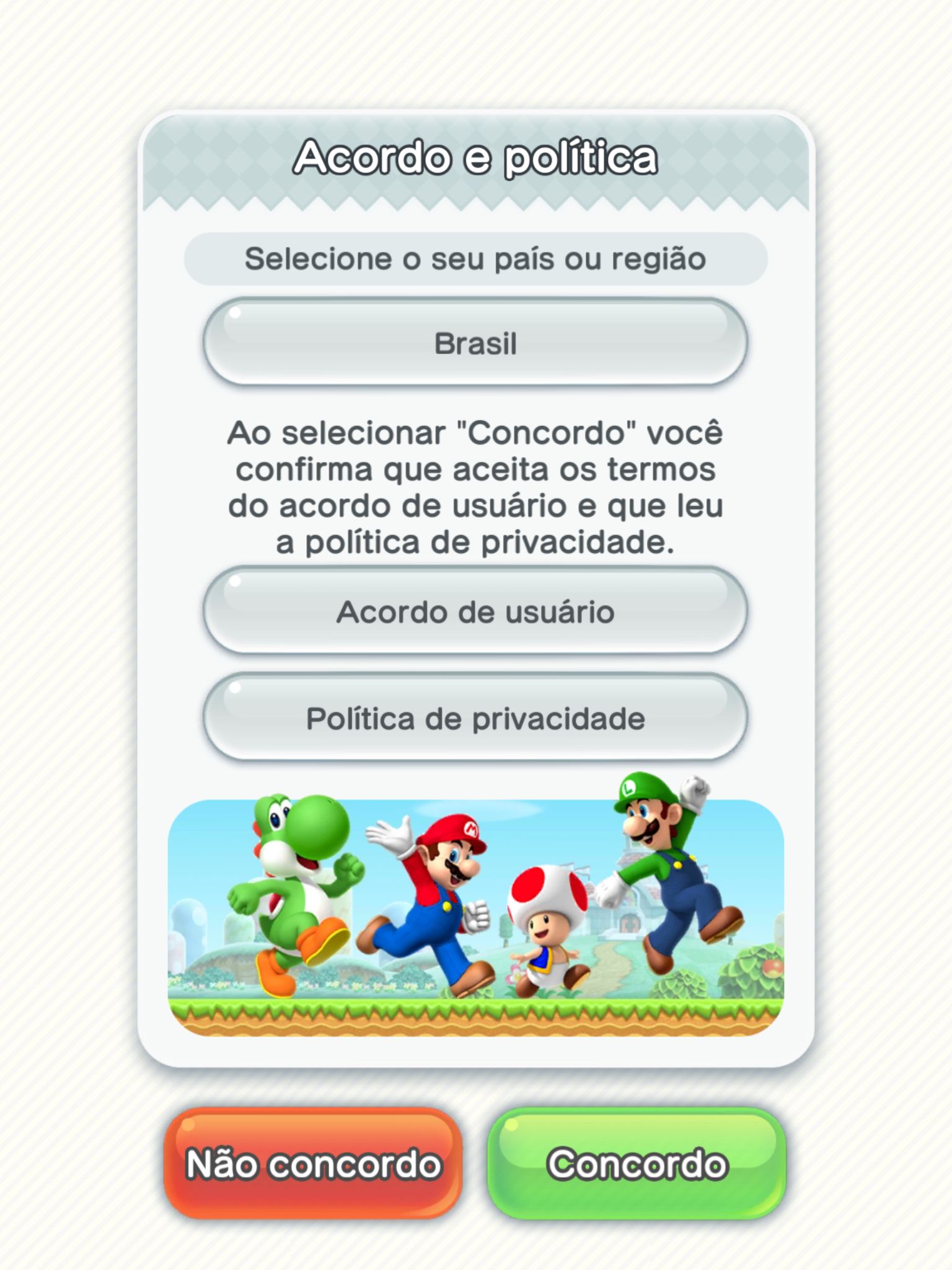

You probably do not remember when you consented to the last game you downloaded for your kid on the app store (if they did not download it themselves). This is no surprise. In fact, it would not be surprising if you do not even remember running your finger through a long text that you did not read and ticking the box at the end. This is because of the 20 apps we analyzed, only 5% (25% – Super Mario Run, Perguntados, PlayKids: Aprender Brincando, Toca Kitchen Monsters e Meu Talking Tom) present their terms of use and their privacy policy as soon as you open the app for the first time.

App Super Mario Run: the user can click and read the “User Agreement” and the “Privacy Policy” and need to actively click on “agree”. Nothing is pre-selected. |

App PlayKids: Ensinar e Aprender: the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy, in English, are in the small grey letters at the bottom of the home screen, which prioritizes inciting the user to create a free account. If you want to escape this, you have to click on the shadow of the “X” on the top left. |

All other apps (75%) only show their policies when you search for them on the settings menu or, if they are not there, on their websites. As a demand from the app stores (App Store and Google Play), these links can be accessed and consulted before downloading the app. But almost no one does it and, in practice, this model means that these apps assume that their “consent” is implicit — because you downloaded the app and are playing it, you must have agreed to the terms of use and privacy policies of the company. This practice seems to be contrary to the express consent demanded by the Brazilian Internet Civil Rights Framework.

3. Most privacy policies are in English.

Another possible difficulty for the establishment of an informed consent is the language: only 6 of the analyzed apps present their privacy policies in Portuguese (Super Mario Run, Galinha Pintadinha, Patati Patatá, Os Pequerruchos, O Show da Luna! Jogos e Vídeos e Meu Talking Tom) — all others are only in English [3].

4. Most privacy policies are general, enforceable to all company’s apps.

It is also worth highlighting that most companies adopt general terms, which can be applied to all of their apps. Only 5 apps (PlayKids: Aprender Brincando, Duolingo, Slither.io, Pou e Subway Surfers) have specific privacy policies, that is, policies that were uniquely thought for that game, its functionality, its audience and the data it collects [4].

Open Questions

The lack of proximity and familiarity of users with the apps’ privacy policies is already a problem for adults. Now imagine when we are dealing with children. The apps that we analyzed are directed, even if not exclusively, to children. As this audience lacks the juridical capacity, it is crucial that the parents or legal guardians of the child grant the consent for it to be valid. This is the first difficulty linked to the parent’s responsibility: read, understand and authorize the terms and policies of the apps used by children.

But how can we say that this point is being met when the users are not even questioned about the content of these policies or have the possibility to partially consent to the offered terms? It is no wonder that many times, the consent seems to be a fiction — a persistent dogma that persists in the legal world. While jurists and designers think of how to revolutionize the obtention of consent, we have to work with what we have until now: these written terms and policies dictate your agreement with the rules of the game and give you an instrument of defense, in case the company undertakes activities that cause you, and mainly your children, any harm.

[1] Read also the Code of Consumer Protection (Law n. 8.078/1990), which prohibits and defines as an abusive practice the execution of services, by the provider, without the “express authorization” of the consumer (art. 39, VI).

[2] “Art. 7. The access to the internet is essential to the exercise of citizenship, and the following rights are assured to the user: (…) VII – the unproviding of their personal data to third parties, including connection and access to internet application logs, except upon free, express and informed consent or in the hypotheses provisioned in law; (…) IX – express consent to the collection, use, storage and processing of personal data, that should happen in a separate manner from the other contractual clauses; (…)”.

[3] In the case of the PlayKids: Aprender brincando app, the privacy policy is in English, but there is an FAQ in Portuguese

[4] In the case of the Meu Talking Tom app, the developer’s policy has some specific clauses for each of their apps only when dealing with the collected data.

Team responsible for the project: Francisco Brito Cruz (francisco@internetlab.org.br), Jacqueline de Souza Abreu (jacqueline@internetlab.org.br) and Maria Luciano (maria.luciano@internetlab.org.br). With the collaboration of Dennys Antonialli and Pedro Lima.

Translation: Ana Luiza Araujo