SPECIAL | Interactivity in children’s apps: with whom? For what?

Children’s apps are seen as a possibility of entertainment in a controlled environment, with appropriate and duly filtered content that allows for parental supervision. Or at least, this is the theory.

On the first post of the Children’s Apps Special (read more here!), we shared the results of our analysis of the interactive features of the 20 most downloaded apps for children in Brazil. In practice, we found a lot of ads, redirection to social networks and in-app purchases, features that are contrary to this view of a problem-free environment.

Our Findings

1. Advertising inside children’s apps is very frequent.

The concern with the exposure of children to advertisements is old and not at all exclusive to the Internet. In this medium, however, the manners in which this exposure happens are more and more unexpected and their impact can be more immediate and subliminal than in other media. For instance, this is the case of ads that allow to directly call phone numbers, download other apps, or visit websites that are pictured in them.

Advertising is quite popular in free apps, appearing in different manners: from the classic banners on the corners of the screen to, and now mainly, videos. Not only do these videos appear frequently between “rounds” of activity in the apps, but they also are used as a bargaining chip. In the apps Once upon a tower, Perguntados, Pou, Meu Talking Tom and Sweet Baby Girl Doll House – Play, Care & Bed Time we noticed that the user (children!) gain restricted functionalities, some of them paid, after watching the ads.

This kind of interactive feature counters the idea established by literature that it is only from 12-years-old on that children start to develop the cognitive defenses which enable them to understand the advertising intentions. About this, it is also worth noting that in Brazil, any advertising directed to children under 12-years-old is considered abusive and prohibited by the Federal Constitution (art. 227), by the Consumer Defense Code (Arts. 36 and 37), by the Children and Adolescent Statute and by the Decree 163/2014 of the National Council for the Rights of Children and Adolescents. [1]

In spite of this prohibition, out of the 20 monitored apps, at least 6 (Perguntados, Football Strike, Pou, Meu Talking Tom, 8 Ball Pool e Duolingo) expressly admit to exposing directed apps. We do not know what happens in the silence of the other apps, as this would demand a technical analysis. The Brazilian company ZeroUm, for example, does not deal with this issue on their privacy policy, but we found ads (that seem to be) directed in our experience with at least one of their apps (Patati Patatá).

2. Many apps offer functions to buy additional content and functionalities through a purchasing mechanism within the app.

It is not unusual to see reports of parents surprised with the expenses made by their children while using the apps. Indeed, we noted in our analysis that the functions to buy extra features within the app is quite common. We observed this type of feature in Snake vs. Block, Super Mario Run, Perguntados, Football Strike, PlayKids: Aprender Brincando, Os Pequerruchos, Once upon a tower [2], Subway Surfers, Pou, O Show da Luna! Jogos e Vídeos e Sweet Baby Girl Doll House – Play, Care & Bed Time.

Knowing that this feature can become a headache for parents and even lead to legal disputes, we observed the different ways in the terms of use that companies use to deal with this problem.

Snake vs. Block and Football Strike, for instance, affirm that only users over 18-years-old can make purchases through the app — but in our experience with the apps, the indicative age was not requested and not even verified. Os Pequerruchos affirms that it ‘assumes’ that all purchases made through the app are of people over 18-years-old or are authorized by the guardians of the underage users. PlayKids: Aprender Brincando, Galinha Pintadinha: Música e Jogos para crianças, Patati Patatá, Os Pequerruchos and Meu Talking Tom only alert to the possibility of altering the settings of devices or activating security measures offered by the app stores.

Concerning this point, we analyzed the terms of use of iTunes and the Play Store. The first has the tool “Request to buy”, which can be manually activated. According to company standards, this feature is automatically activated for children under 13 years old — but it is unclear how this happens: does the child has to own an account at the store or own the device? [3] The Google Play Store, in its turn, allows the setting of authentication barriers, that is, the need to insert certain information such as a password to make the purchase. This feature is automatic in the case of apps developed for children up to 12 years old.

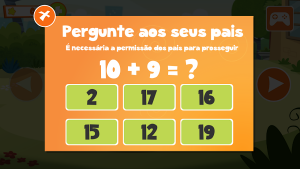

Some apps have already included security mechanisms against potential problems of this functionality in the app’s own code. In O Show da Luna! Jogos e Vídeos and PlayKids: Aprender Brincando, when you select items for sale, a screen pops-up showing a mathematical equation to be solved with the title “Ask your parents”. The user is only redirected to the purchase after the equation is solved. PlayKids: Aprender Brincando, Toca Kitchen Monsters and Galinha Pintadinha: Músicas e jogos para crianças also have similar mechanisms. In our test, Patati Patatá used this mechanism only some of the times.

3. Another common feature is the linking to social networks

This feature appears in two distinctive manners. Frequently, the possibility of using a social network account, such as Facebook or Twitter, to login in the app is given to the user. We observed this feature in Super Mario Run, Football Strike, Perguntados, PlayKids: Aprender Brincando, Subway Surfers, Pou, Meu Talking Tom and 8 Ball Pool. If used, the app starts to have access to the personal data of the user stored in the social network. We will discuss the issues regarding personal data on the third post of this series (18/10).

Another manner is the redirection to other social networks. In Meu Talking Tom, when you select a generic video item, without any warning the child is redirected to the character’s YouTube channel. In addition to being taken outside the app, she is exposed to other advertising videos and, with only one click, to all unfiltered YouTube content.

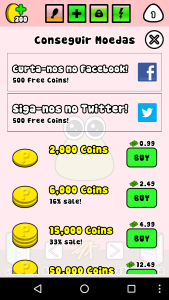

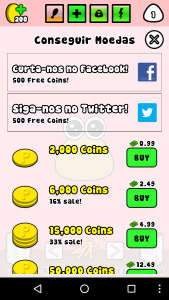

Here, our experiences with the apps Perguntados, Football Strike, Subway Surfer, Pou and 8 Ball Pool are also worth highlighting. In these apps, certain functionalities can be “purchased” by logging into Facebook: the user’s personal data obtained from their Facebook profile becomes the bargaining chip for obtaining restricted functionalities in the app.

In Pou, for instance, the user can trade Facebook likes and follows on Twitter for coins, that can be used inside the app.

Our findings accentuate the need for consistent, clear and easily accessible information about the purchasing, social network interaction and advertising functionalities in the apps so that parents can make informed decisions about allowing their children to use application with these capacities.

[1] The Economist Intelligence Unit. “The impacts of banning advertising directed at children in Brazil”, p. 35. August 2017. Available at <http://criancaeconsumo.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Relatorio_TheEconomist_.pdf>. Accessed on 02.10.2017.

[2] This information appears in iTunes and the Play Store. In our experience testing the apps, we did not see this option.

[3] In 2014, according to the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC), Apple was forced to reimburse parents for purchases made by unauthorized children.

EXAME, “Apple reembolsará compras de apps feitas por crianças”, Exame, January 15th 2014, available at <https://exame.abril.com.br/tecnologia/apple-reembolsara-compras-de-apps-feitas-por-criancas/>.

Team responsible for the project: Francisco Brito Cruz (francisco@internetlab.org.br), Jacqueline de Souza Abreu (jacqueline@internetlab.org.br) and Maria Luciano (maria.luciano@internetlab.org.br). With the collaboration of Dennys Antonialli and Pedro Lima.

Translation: Ana Luiza Araujo