InternetLab files amicus curiae brief in a Federal Supreme Court case that can change Internet intermediaries’ liability regime in Brazil

Read below the translation of the article “Changing the liability regime of internet intermediaries” [in Portuguese] published on Jota’s website and signed by Dennys Antonialli (InternetLab’s Executive Director) and Thiago Oliva (Head of Research on Freedom of Expression).

Many internet platforms, like Facebook, Twitter and Youtube, operate based on the publication of content created by third parties. Thus, the liability for potential damages caused by these contents has become, over the years, a sensitive issue: on the one hand, arguments related to the protection of rights such as freedom of expression and access to information justify regulatory models that exempt internet platforms from any liability for third party content before there is a judicial decision considering such content illegitimate or illegal – thereby ensuring that their policies and terms of use support a wide dissemination of all sorts of content; on the other, arguments on the side of rights like privacy, honor and image, justify regulatory arrangements that create more situations under which it is possible to render internet platforms liable for damages caused by third party content, encouraging them to implement more restrictive policies, in an attempt to avoid economic risks.

After the Brazilian Internet Bill of Rights (Marco Civil da Internet, or MCI, in Portuguese) was passed, in 2014, this issue was solved in Brazil. Its article 19 adopted the liability regime centered around judicial orders, what means internet platforms (“intermediaries” or “application providers”) may be rendered liable for content posted by their users only in case they fail to take content down after being notified of a court order requesting the removal of such content. The law established exceptions for cases involving copyright violations (art. 19, paragraph 2) or non-consensual dissemination of intimate images (art. 21).

The constitutionality of article 19 was, however, questioned by the Extraordinary Appeal n. 1,037,396, filed by Facebook Brasil before the Federal Supreme Court. The case’s rapporteur, Justice Dias Toffoli, recognized its general repercussion, opening way for a change in the intermediary liability regime adopted by the MCI.

On December 11th, InternetLab filed an amicus curiae brief on the case before the court. In the brief, InternetLab presents data and research conclusions that indicate that, in case the liability regime centered around judicial orders adopted by the MCI is declared unconstitutional and consequently substituted by a liability regime centered around extrajudicial notice, the exercising of rights such as freedom of expression and access to information on the internet may be severely restricted in Brazil.

Understanding the case

The case involves a fake profile created on Facebook. The plaintiff, who argued being harmed by the creation of the fake profile using her name, requested its removal, the delivery of data for the identification of the person behind its creation, in addition to compensation for moral damages. The lower court’s decision granted the requests for the removal of the profile and the delivery of the data necessary for the identification of the profile’s creator. However, it turned down the request for compensation based on art. 19 of the MCI. According to the decision, art. 19 sets forth that application providers – like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, etc – are only liable for content generated by third parties if they do not comply with a judicial decision demanding its removal.

However, when analyzing the appeal presented by the plaintiff, the Second Civil Law Appeals Panel of Piracicaba’s Appeals Court, in the state of São Paulo, amended the decision in order to render the platform liable in this case, arguing that the removal of the fake profile only after a specific court order demanding it would mean exempting application providers of “each and every compensatory liability”, in violation of the Consumer’s Defense Code.

The platform filed an extraordinary appeal before the Federal Supreme Court pleading for a decision on the constitutionality of the MCI’s article 19, which was not enforced by the decision of the Second Appeals Panel.

Amicus Curiae brief: the main arguments

At first sight, it may seem that the case is only discusses civil law issues, simply aiming to define the moment from which internet platforms can be considered liable for content generated by third parties. However, defining internet platforms’ liability regime goes way beyond, as it has direct consequences to the exercise of fundamental rights, like freedom of expression and access to information.

This happens because, as we will show, the liability regime centered around extrajudicial notice (i) is mainly adopted by countries with political regimes which are considered authoritarian, like China, Venezuela, Iran, Russia, and Ruanda; (ii) waives the judicial assessment of removals requests’ legality, which may result in arbitrary removals; and (iii) enables the use of abusive or illegitimate extrajudicial notice as means to constrain and censor.

InternetLab’s brief can be read in full here [in Portuguese]. Below, we present a summary of our main arguments:

1) The intermediaries liability regime centered around extrajudicial notice (i) is mainly adopted by countries with political regimes which are considered authoritarian, like China, Venezuela, Iran, Russia, and Ruanda;

In these countries, the regulatory regimes in force are backed by practices that privilege control of content circulation over freedom of expression and access to information. The chart below presents the main features of liability regimes for internet service providers adopted in these countries:

| Country | Freedom House Classification | Legislation | Intermediary Liability Regime | Who is entitled to demand content removal |

| China | “Not free” (14/100) | Tort Liability Law, art. 36 Cybersecurity Law |

Subjective liability, after extrajudicial notice (general rule) Objective liability (dissemination of “false” information which may disrupt “economic and social orders” and national security) |

Interested party (victim of rights violation) Public authorities in general |

| Irã | “Not free” (17/100) | Computer Crimes Law 2009, arts. 21 and 23 | Subjective liability, after extrajudicial notice (administrative) Objective liability if intermediary fail to filter content which “results in crime” on the internet |

Committee to Determine Instances of Criminal Content, government body formed by representatives of a number of state agencies |

| Ruanda | “Not free” (23/100) | Law No. 18/2010 Relating to Electronic Messages, Electronic Signatures and Electronic Transactions, art. 14 Law No. 24/ 2016 governing Information and Communication Technologies |

Subjective liability, after extrajudicial notice (user) Intermediary shall not be held liable for removals based on unfounded notice |

Interested party (victim of rights violation) |

| Rússia | “Not free” (20/100) | Federal Law No. 149-FZ of July 27, 2006 on Information, Information Technologies and Protection of Information | Subjective liability, after extrajudicial notice (administrative) | Roskomnadzor (agency under control of the Ministry of Telecom), prosecutors, police, drugs control agency, consumer protection agency and courts of law |

| Venezuela | “Not free” (26/100) | Law of on Social Responsibility on Radio and Television (RESORTE-ME) | The law does not specify what triggers liability | CONATEL, agency responsible for regulating telecommunications |

2) Judicial assessment is essential to ensure that unfounded removal requests do not end up suppressing legitimate content

Dissenso.org, a project developed by InternetLab, has an extensive repository of judicial decisions [in Portuguese] that involve the exercise of free speech in the digital environment. This database is fed weekly, being composed, above all, by interlocutory decisions and rulings mentioned in courts’ press rooms or broadly disseminated by the media. Even though it is not an exhaustive databank, Dissenso.org’s repository paints a representative picture of the main case law tendencies on freedom of expression and access to information in the digital environment in Brazil.

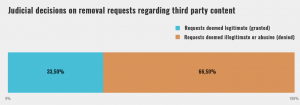

Considering the data generated by this repository, which had 152 catalogued decisions at the moment InternetLab presented its amicus curiae brief, in only 33,5% of the cases involving content removal requests on the internet these requests were either granted or confirmed by higher courts – that is, in more than 60% of cases, the removal requests were considered illegitimate, unfounded, or abusive, and the immediate compliance by the platforms would result in the removal of legitimate content. In this sense, the protection from liability until the courts assessment encourages platforms to keep content online, instead of preemptively censoring it.

3) The regulatory regime in force in Brazil prevents the use of extrajudicial notifications as means to limit expression

According to researches developed by InternetLab, especially those related to the publishing of humorous content online, politicians, authorities, prominent people and public institutions can use extrajudicial notifications, legal actions to identify internet users and other legal strategies with the goal of censoring criticism directed at them, hindering the exercise of free speech and access to information on matters of public interest.

These strategies can stifle the public debate: the existence of a lawsuit threat intimidates both the author of the critique as well as the individual or company responsible for the media in which it was published, creating an economic stimulus for the content to be removed. These strategies also work as a “warning” to other parties interested in the debate: acid criticism will be the target of costly lawsuits, so it is best to think twice before daring to express yourself freely.

In case the intermediaries liability regime adopted by the MCI is declared unconstitutional, the ones who are interested in silencing criticisms in the public sphere would have an additional option to achieve their goal: they could notify internet platforms extrajudicially, threatening them to remove content that they consider offensive to their honor and image in order to refrain from asking for compensation before the courts.

By Dennys Antonialli, Ph.D in Constitutional Law, University of São Paulo and InternetLab’s Executive Director and Thiago Oliva, Head of InternetLab’s Freedom of Expression research area.

Translated by Ana Luiza Araujo and Thiago Oliva