Black and indigenous journalists receive offenses when they stand against racism

Warning: This article presents explicit excerpts of misogynistic and racist content. We decided not to censor them because we understood it is important to exemplify how violent the debate is on social media, how violence against women journalists is spread, what terms are frequently used and how we can identify this kind of violence.

Article originally published by AzMina magazine, by Jamile Santana and Laís Martins.

Women journalists in general face challenges when they express their positions on Twitter. When it comes to black and indigenous women, we see even more troublesome aspects. Besides the misogyny and gender violence that target them only for being women, these groups are under attacks that aim to discredit the fighting against racism and for the constitutional rights of indigenous peoples.

Accusations such as “black woman discourse”, “victimization” and “opportunist” are frequently found on tweets addressed in response to these professionals, as shows the data survey carried out by AzMina Magazine, InternetLab and Núcleo Jornalismo, in a partnership with Volt Data Lab and INCT.DD, and with the support of International Center for Journalists (ICFJ).

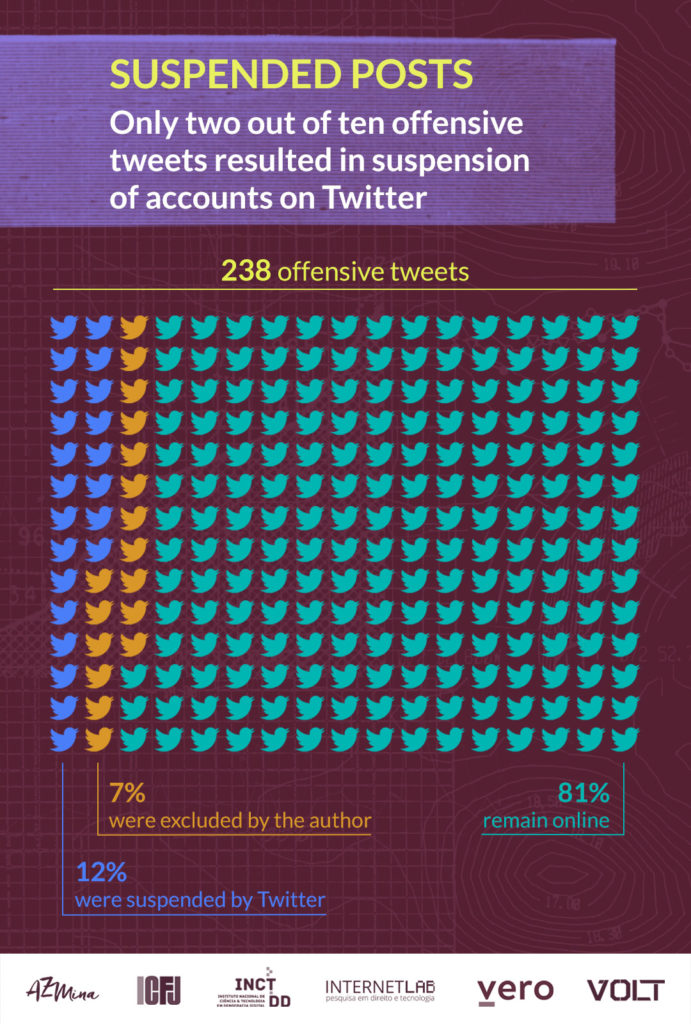

The second report on the series about gender violence against journalists analyzed nearly 240 offensive tweets directed to a group of 26 black and indigenous women journalists. One of our findings shows that only two out of ten offenses were removed by the social media platform. The most recurrent terms are divided in the categories of racism, personal offense, offense to the exercise of the profession, intellectual discredit, sexism, physical threat and sexual harassment.

Offenses as “partial journalist”, “biased” and “manipulative”, “communist” (in a bad sense), “loser” and “ridiculous” are the most frequent among the tweets addressed to the analyzed profiles. The attacks always happen when a user disagrees with the information or point of view published by the journalists.

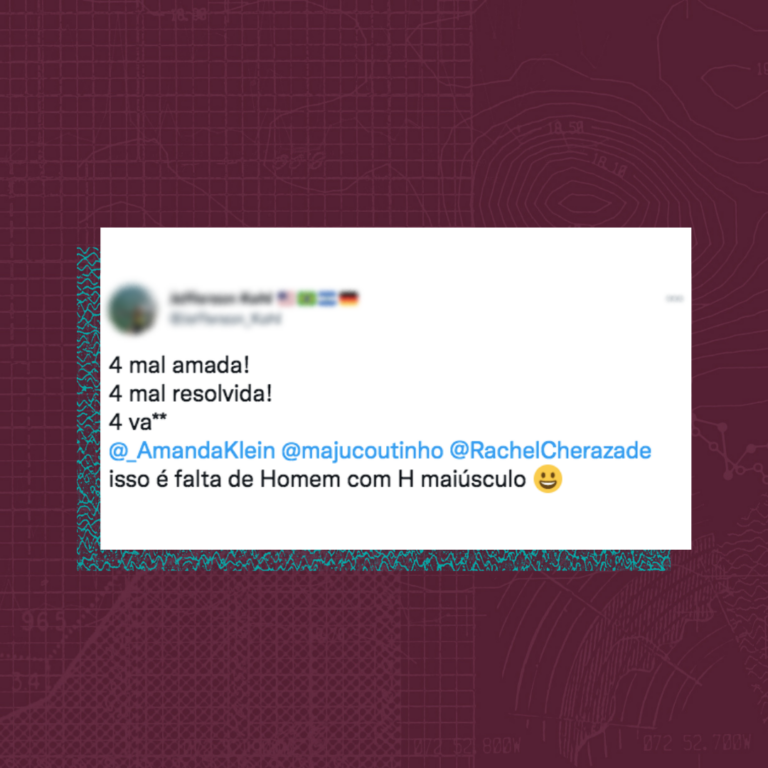

Other phenomenon we identified was the use of misogynistic sentences to discredit and silence the professionals. The offensive messages contained expressions as “go wash the dishes”, “go take care of your family” or “unloved”. Terms to intellectually discredit women were also identified, as “crazy”, “stupid”, “sick”, “wacko” and “dumb”, for example.

Anti-racist fighting

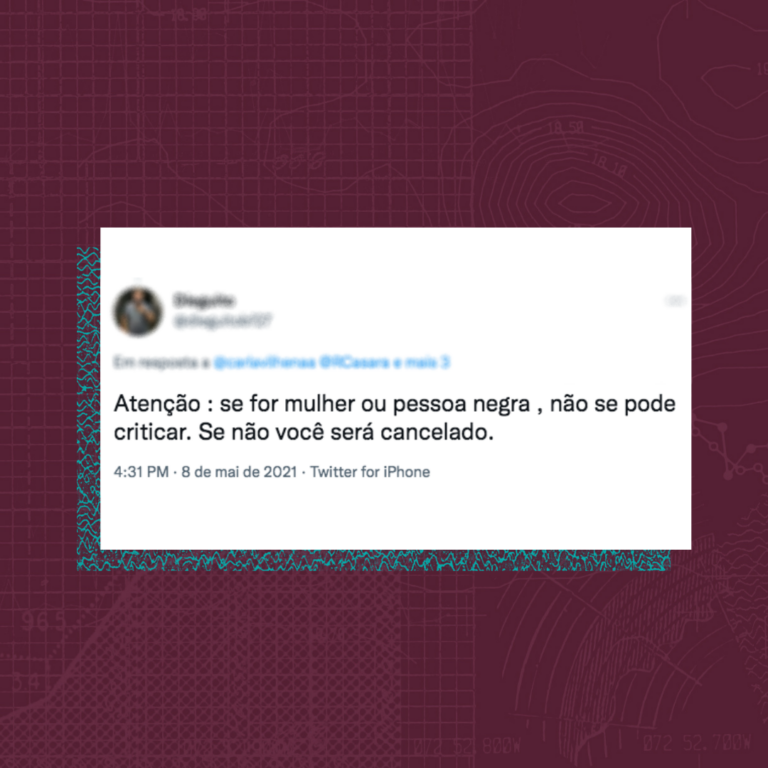

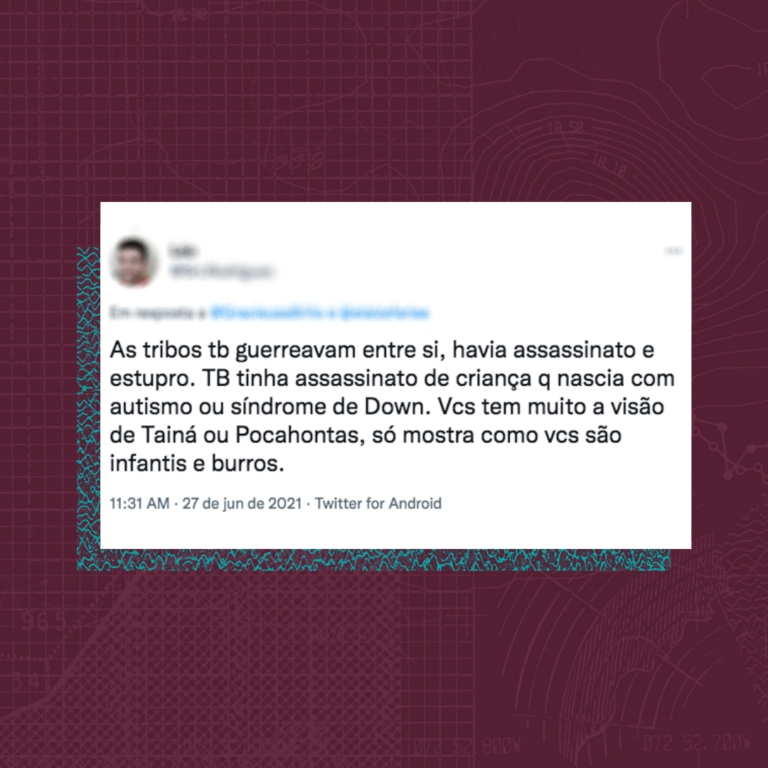

Black women are frequently attacked when they stand against racism. In the messages, aggressors relativize anti-racist positions, suggesting, for example, that “one can no longer criticize a black person” or that “black people can also kill white people”.

Last year, the journalist Flávia Oliveira, commentator at Globo News and columnist at O Globo and CBN newspapers, posted a tweet addressing the episode in which the statue of Borba Gato was set on fire in São Paulo. On the message, she, who is a black woman, recommended reading the book “Escravidão 2”, by Laurentino Gomes, in order for people to find out who the historical character targeted by the anti-racist protest had been. The journalist was attacked with a series of racist and misogynistic offenses, and the content remains online.

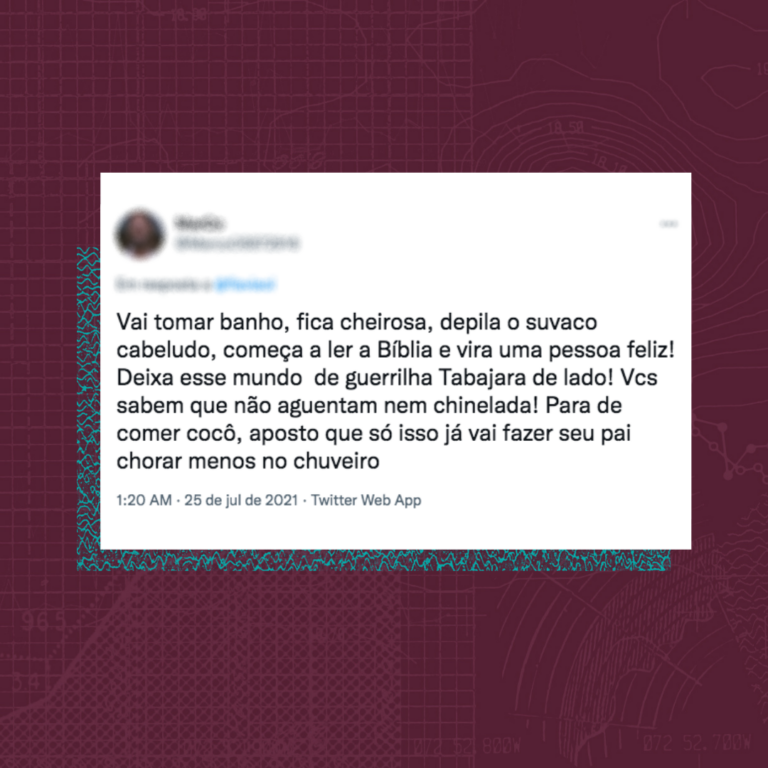

world! You know you can’t even take a whipping! Stop eating shit, I bet this alone will make your father stop crying in the shower”.

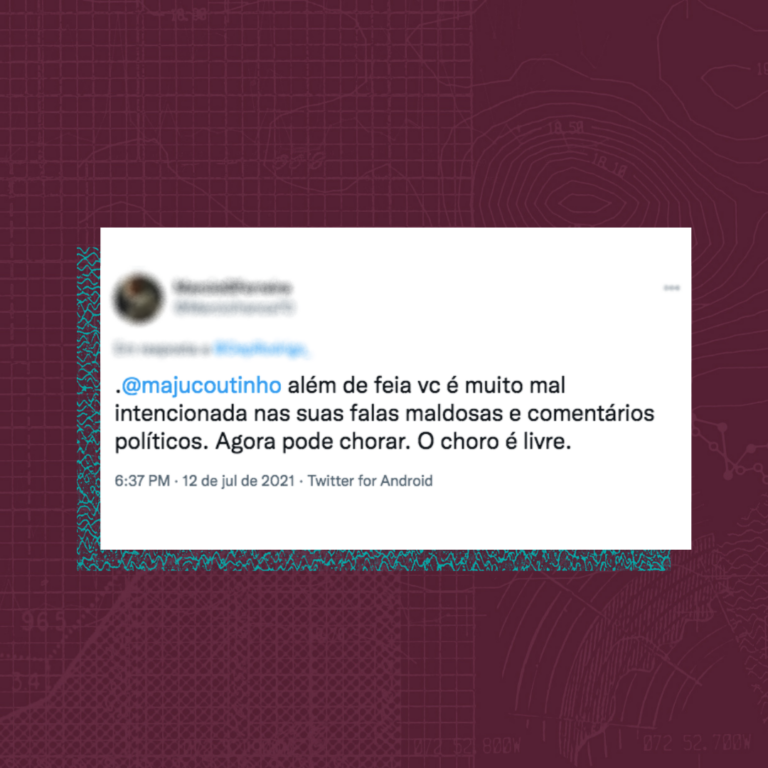

In certain cases, though, the attacks are not even responses to posts published by the professionals. When the journalist and presenter Maju Coutinho is on air on TV Globo, for example, she receives unmotivated offenses. In some cases, the attacks are followed by physical threats. The monitoring also suggests that there is a harassing behavior coming from some users: we found ten attacks to her originating from one single user. All the contents can still be found online.

Professionals working for media outlets of national range, especially television, are more exposed to the offenses. Black journalists from online or print media, however, are also victims of organized attacks, as reports Gabi Coutinho, a journalist at O Estado de São Paulo newspaper and a member of Coletivo Lena Santos, an organization of black journalists, women and men, from the state of Minas Gerais.

“The attacks I receive and have received, almost all of them targeted gender and race issues”, she said. In one of those experiences, they spread a picture of her after a report she wrote about negationism. “The goal was to make my face known and marked to other users of the social media”, she said.

By that time, Gabi counted on the support of Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (Abraji), of the newspaper she works for, and of Twitter. But the journalist wonders how to search for support from platforms and social media, “knowing they reproduce what we call structural racism”. And she concludes that looking for support is important “for us to continue existing in these essential spaces”.

Cecília Oliviera, an investigative journalist, receives attacks on her Twitter account almost every day. Oliveira, who is also founder and director of Instituto Fogo Cruzado, focuses her coverage in the public security field, especially on firearm and drug trafficking, themes that are majorly covered and debated by men.

“What would have been a criticism to my work turns into a personal criticism, with attacks to sexuality and race. Those are offenses targeted to what you are as a person, exactly because a lot of the aggressors work in attacking the person, not the idea”, she affirms. More than half the offensive terms found on the analysis are personal offenses and are not related to the journalists’ professional practices.

Read also: Women journalists receive more than double the offenses of their male counterparts on Twitter

Indigenous fighting

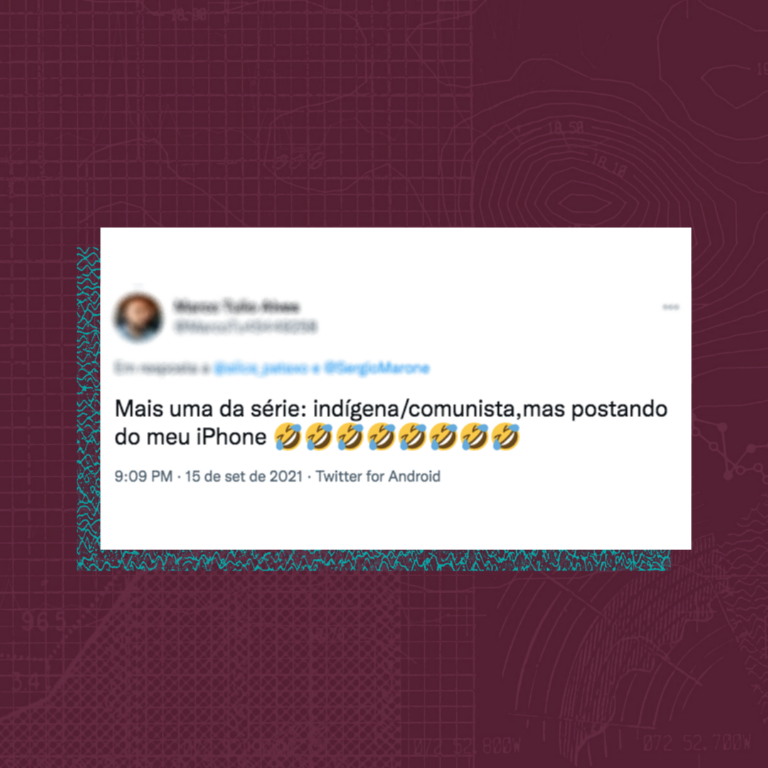

Indigenous journalists are also attacked when they address topics as indigenous land demarcation and policies. Questioning and discrediting indigenous identity have been used for a long time as a silencing strategy – for instance, when indigenous persons are questioned for occupying urban spaces, using technologies and speaking foreign languages.

After posting a tweet showing the map of Brazil completely marked as an indigenous land, the journalist Elaíze Farias, reporter and co-founder of Amazônia Real, was attacked by many users that tried to discredit the fight for the recognition of indigenous territories.

down syndrome. You have the idea of Taina or Pocahontas, it only shows how stupid and childish you are”.

“When indigenous women start talking about their experiences, their social and cultural practices using one of the many tools resulting from technological development, when they speak out and denounce injustices and violations to which they are subjected, that causes discomfort and anger in non-indigenous persons”, she stated.

The indigenous journalist Alice Pataxó is also targeted by offensive attacks when she covers events that discuss the access to fundamental rights by indigenous peoples. In one of the episodes, she published the picture of a hearing about Marco Temporal das Terras Indígenas (a case discussed in the Supreme Court about the demarcation of indigenous lands), and a user criticized the journalist for having access to a cell phone device.

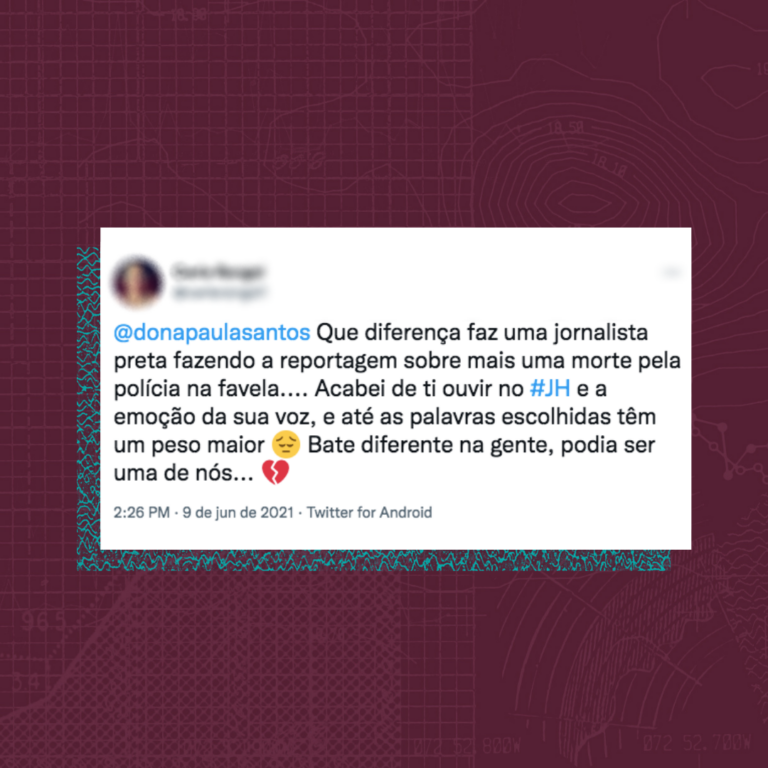

Aquilombamento on social media

In spite of the hostile scenario and in response to the violence, our survey found 157 tweets supporting black women in a total of 2,204 messages that included terms about race.

The union of black people to the strengthening of the individuals in a collective way is known as “Aquilombamento strategy”. Quilombos were fundamental devices in preserving the identity, the dignity, the culture and the mental health of the black population during the slavery period, as notes the psychologist and MA in Clinical Psychology at Federal Fluminense University Lucas Vega, in the article: “Descolonizando a psicologia: notas para uma Psicologia Preta” (Decolonizing psychology: notes for a black psychology). “The encounter of black men and women is a cure”, he wrote.

#JH and the emotion in your voice, and even the words chosen have a greater weight. It strikes us differently,

it could have been one of us…”.

To Fernanda K. Martins, anthropologist and research coordinator at InternetLab, social media have an ambiguous place in the professional practice of black and indigenous people.

On the one hand, there is more space for these people to be heard, to reach a larger audience and to find spaces for cure when they deal with their peers”, she affirms. On the other hand, Martins adds that platforms in general have difficulties in dealing with attacks. According to her, that happens in part because platforms cannot identify the context of attacks, which prevents them, for example, from excluding certain contents.

“Improving this kind of moderation is urgent, because social media can keep online contents that violate Brazilian laws”, Martins affirmed. This is the case of some explicitly racist tweets we found throughout the research.

Offensive contents remain online

Only two out of ten offensive posts identified by our analysis were excluded – some of them by Twitter, and some by the users themselves. It is worth noting that our analysis did not follow the platform’s terms and policies. The company follows its own guidelines to identify potentially harmful posts.

Elaíze Farias reports that, when she receives this kind of attack on social media, she tries to shield her mental health by using a specific strategy: “I don’t usually read posts and retweets. I usually only interact with people I follow on Twitter, so the attacks get lost in the debris. The important fact is to get the message across”, she said. But she argues that digital platforms should adjust their strategies to combat violence. “I think we could have some moderation, especially for lies and racist posts. Some means of identifying who the authors are, because racism is a crime in the country. On the other hand, we cannot be naive and hope this will happen in a short period of time”.

After taking a course on social media interaction, Cecília Oliveira also changed her way of dealing with attacks and offenses. “Before, I used to get really shaken when I was attacked, so, now, when I know there is a tweet with potential to attract haters, I silence the tweet and don’t go back to it”. Besides that practice, she does not share the attacks she receives and uses filters that are available on Twitter to limit, for example, notifications from users whose emails and phone numbers are not verified.

But the network’s tools are not always satisfactory. The journalist remembers that last September she started receiving systematic attacks from a user that answered to all her tweets with a print of the video ‘Nega do cabelo duro’. When she reported it to the platform, the journalist received a notification after a few days, informing that the content did not violate the platform’s policies.

I complained to Twitter about the platform’s feedback, saying that those were systematic attacks from the same account, racist offenses, and that I had received that feedback, and then the Twitter staff sent me an email. They thanked me and I suppose they changed it later”, said the journalist, who has 173 thousand followers on Twitter.

In a note, Twitter informed that “they have a policy against hate speech that forbids tweets with dehumanizing language content based on religious affiliation, caste, age, disability, serious disease, race, ethnicity or national origin, gender identity or sexual orientation. The policy for abusive behavior forbids engaging or inciting the harassment of someone”.

The platform also stressed that it is not always clear if the contents were produced with intent of harassing or attacking a person based on their “protected category status” and, because of that, it might be necessary that the users themselves report it. “To help our team to understand the context, sometimes we need to hear the person who has been directly affected, to guarantee that we have the necessary information before we take corrective measures, which may comprise from exclusion and/or visibility reduction of a tweet, to permanent suspension of the account”, states the note.

Methodology

We composed a list of journalists with different gender, race and ethnicity profiles and different sexual orientations to be monitored online, aiming at building an analysis that would allow us to articulate social markers. This list included 200 journalists (133 women and 67 men), and mixed professionals working for different outlets of the Brazilian media, in different regions of the country and, at the same time, who were in different phases of their careers.

We collected tweets and retweets that mentioned the monitored journalists and that contained at least one of the words present in a list of terms that could be used on offensive posts. This lexicon includes offensive terms, whether misogynistic, racist or homophobic, and was built by linguists, journalists and other specialists.

The tweet collection was carried out from May 15th to December 27th, 2021. We collected a total of 7,082,947 tweets and retweets directed to women and men journalists.

Once the collection was concluded, we separately analyzed tweets directed to black, indigenous and Asian descendant women journalists. As it was not possible to perform a qualitative analysis of all the tweets and retweets mentioned, we opted for only analyzing the tweets that had at least one like and/or retweet as engagement. We considered 2,455 posts with potentially offensive terms. The manual analysis was important to remove “false positives” that could have been incorporated by quoting words present in the lexicon, but that were out of context and sometimes not in fact offensive.

To make sure there was a common understanding among the researchers about what in fact constituted an offense and what was merely criticism, we analyzed collectively the first 100 tweets. Besides that, tweets that had more complex contexts, and that could not easily be labeled by a researcher alone, were analyzed by more than one researcher.

Finally, the offensive terms we found were classified in categories: racism (which considered offenses and discrediting the anti-racist movement), personal offense (swear words and aggressions according to the personal context of each journalist), offense to the exercise of the profession, intellectual discrediting, sexism, physical threat and sexual threat.

______________

*The project “Understanding how influence operations across platforms are used to attack journalists and hamper democracies” is carried out in a partnership of InternetLab, INCT.DD, Vero Institute, DFR Lab, AzMina and Volt Data Lab. The research is funded by Partnership for Countering Influence Operations, from Carnegie for International Peace, and also counts on support from International Center for Journalists (ICFJ), via Volt. The study aims at understanding the patterns of attacks to journalists on digital environments, with a special focus on gender and race issues.