InternetLab Reports – Public Consultations No. 04

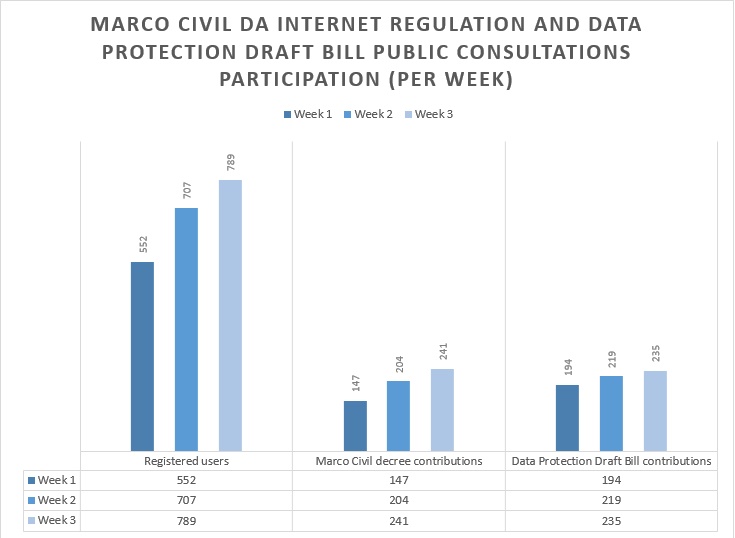

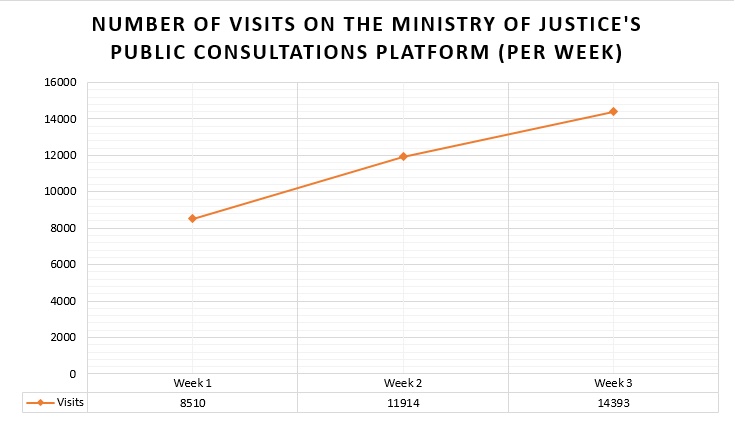

The public consultations about the regulation of Marco Civil and the Data Protection draft bill continue. Check how the third week was, in terms of numbers and controversial topics.

Numbers and statistics

Marco Civil regulation: access of “account information” by “administrative authorities”

An issue discussed in the regulation of Marco Civil is how the “access logs” and “account information” of Internet users should be retained and provided when requested by third parties. In order to preserve evidence to identify users, the law requires that applications providers (search engines, social networks and all the services we have access to through the network) and telecom operators keep records of activities and of users’ connections, but this information remains confidential. Only a judge is entitled to order the delivery of such records to third parties, for privacy reasons.

On the platform, Francisco Brito Cruz, director of InternetLab, created a topic to discuss the issue. His comments were endorsed by Rafael Zanatta, project lead and researcher at the same institution, and by the participant Mário Augusto. InternetLab, keeping with its mission of fostering public debate on law and technology, encourages individual contributions of its members (directors, researchers and interns). The idea is to collaborate with the improvement of the discussion platform and to endorse academic pluralism within its research team.

Brito Cruz discusses paragraph 3 of Article 10 of the Marco Civil. This provision deals with access to users’ account information by “administrative authorities” (such as full name, address, email and other information the user may have provided to telcos). These data do not enjoy the same confidentiality level as the records of activities and connection.

Art. 10. The retention and the making available of connection logs and access to internet applications logs to which this law refers to, as well as, of personal data and of the content of private communications, must comply with the protection of privacy, of the private life, of the honor and of the image of the parties that are directly or indirectly involved.(…)

3°. The provision of the caput of art. 10 does not prevent administrative authorities to have access to recorded data that informs personal qualification, affiliation and address, as provided by law.

Brito Cruz expressed three concerns. Firstly, that the regulation needs to differentiate the data that is protected due to privacy rights – whose disclosure depends on a court order – from other sorts of “account information” that “administrative authorities” can request without a court order. This is important to ensure the Marco Civil privacy protections on application and connection logs:”[t]o achieve the protections provided by the caput (…) it should be clear in the regulation that account information can only be provided with the indication of a username or other information of the users’ service account in question “. If understood otherwise, administrative authorities in possession of an application log (IP address, for instance) could request for account information related to this access log without a court order. This would mean that they could identify a user without a court order.

Secondly, the contribution asks for a definition in the decree about who the “administrative authorities” that may require account information may be. According to Brito Cruz, the choice of these authorities, to be made in the decree, must follow the principle of purpose. There should be a connection between the role of the administrative authority and its request for account information. In addition, the request itself should be justified. The idea is to formalize the control on authorities and prevent vague requests.

Finally, Brito Cruz says it is a right of the user to be informed about the collection, use, storage, treatment and protection of their personal data provided in their accounts (protected by the Civil Marco in his art. 7, section VIII). Whenever an administrative authority requires account information, the citizen must be informed, even if it is a criminal investigation. Obviously, there will be exceptions when confidentiality is necessary, but these cases should also be made clear in the decree.

Data protection: what is an anonymized data set? Should they be protected as personal data?

The participant Bruno Bioni (Master in Law at USP and Visiting Researcher at the Center for Law, Technology and Society, University of Ottawa) made contributions on the platform analyzing the difference between personal data (PII) and anonymized data (Non-PII) (sections I and IV of Article 5 of the draft bill).

Bioni points out to the important balance between the protection of Internet users’ personal data and possibilities for innovation and improvement of services through the treatment of anonymized data.

According to him, the draft bill leaves the door open for abuse by defining anonymized data as non re-identifiable data “taking into account the means that can be reasonably used to identify a data subject”.

The problem is that data which may be considered anonymized under this definition (and thus not protected as personal data) could be re-identified as long as such re-identification was not pursued by means understood as reasonable. The participant suggests a better definition of those “reasonable means”.

Bioni suggests that anonymized data should be included in the scope of protection of the law. His idea is that the protection of personal data should be also extended to anonymized data sets. The difference would be that the anonymized data sets would not require the user’s consent for processing and treatment. Bioni argued that this would ensure user privacy and market innovation at the same time, since innovators would not have to deal with consent as an “obstacle” in this case.

He states that the latter suggestion is in line with the perception of experts that actually no data can be 100% anonymized. For this reason, protection to anonymized data sets should not be excluded, since the “danger” of re-identification will always exist.

To comment on this issue, InternetLab invited Jamila Venturini and Luiz Fernando Moncau, from the Center for Technology and Society – CTS at FGV DIREITO RIO.

After all, is anonymous data really outside the scope of the draft bill?

Commentary: Jamila Venturini and Luiz Fernando Moncau (researcher and coordinator of the Center for Technology and Society – CTS at FGV DIREITO RIO)

On the one hand, the current wording of Article 5, paragraph I, of the draft adopted a comprehensive definition of personal data – including data related to an identified or identifiable person. On the other hand, in section IV of that article, anonymized data are defined separately, as data sets in which it is not possible to identify the subject by using reasonable reidentification means. Once Article 1 states that the law only applies to the processing of personal data, there seems to be a general exception to anonymised data. Although there may be different interpretations on this point, this apparent conflict can lead to legal uncertainty with regard to the scope of a future Personal Data Protection Act, especially if we consider that the practice of anonymisation of data after a certain period is already a market practice.

In addition, this type of exception can give rise to a relativization of the protection afforded to privacy, especially where re-identifying practices are used to identify the data subject. Importantly, experts have pointed to the weakness of the concept of data anonymization. To Cory Doctorow, “Where a regulation states that any data is “anonymous”, it is disconnected of the best theories of computer science” (click here for more).

A good practice would be to establish clear criteria to determine what would really be considered anonymous data and ensure that an authority responsible for implementation of the law – a competent body, as determined in the current text of the draft – can review these criteria based on future technological developments. Another alternative would be to impose liability on anyone who is responsible for employing flawed anonymization techniques for any privacy harm damages. If, on one hand, this could bring an extra incentive to data deletion or effective deanonymization, on the other, it could discourage big data practices. With the evolution of technology, will there be any databases that can’t be truly deanonymized? And if not, does it really make sense to exclude them from the scope of a data protection law?

The text of the bill considered, is the difference between anonymous and personal data is really only whether or not to re-identify?

Commentary: Jamila Venturini and Luiz Fernando Moncau (researcher and manager of the Center for Technology and Society – CTS at FGV DIREITO RIO)

A first interpretation suggests that personal data that would be able to lead directly to an identifiable person (such as a ZIP code, an IP address, a unique identifier cell phone, etc.), while the anonymous data would be the data that is identifiable not even with employment of “susceptible means to be reasonably used to identify the holder.” However, note that the current definition of anonymous data seems to suggest that there can always be ways – unreasonable – for re-identification. If this is the case, the difference between personal and anonymous data ultimately resides in the conceptualization of what would be reasonable means: if re-identification is possible by reasonable means, we would have personal data, otherwise, we would have anonymous data .

In this case, it seems appropriate that the Legislative bodies provide more specific criteria as to what can be understood as “reasonable means” to identify the data subject. The problem with this alternative is to start a long dispute in the legislative field, with significant bargains on the interpretation criteria. As in Europe, the lobbying of private interests is already moving towards affirming the benefits of Big Data and the need to exclude anonymous data from any protection. The benefits of these activities are unquestionable, but the protection of rights in a context where technologies for invasion of privacy are developed in such a fast pace deserves special attention. And that is the purpose of the law. As in Europe, this promises to be a point of much controversy during the legislative process. More information about anonymization techniques and their debate in Europe can be found here.

Authors: Jonas Coelho Marchezan, Francisco Brito Cruz, Dennys Antonialli and Mariana Giorgetti Valente