Can WhatsApp groups become police cases?

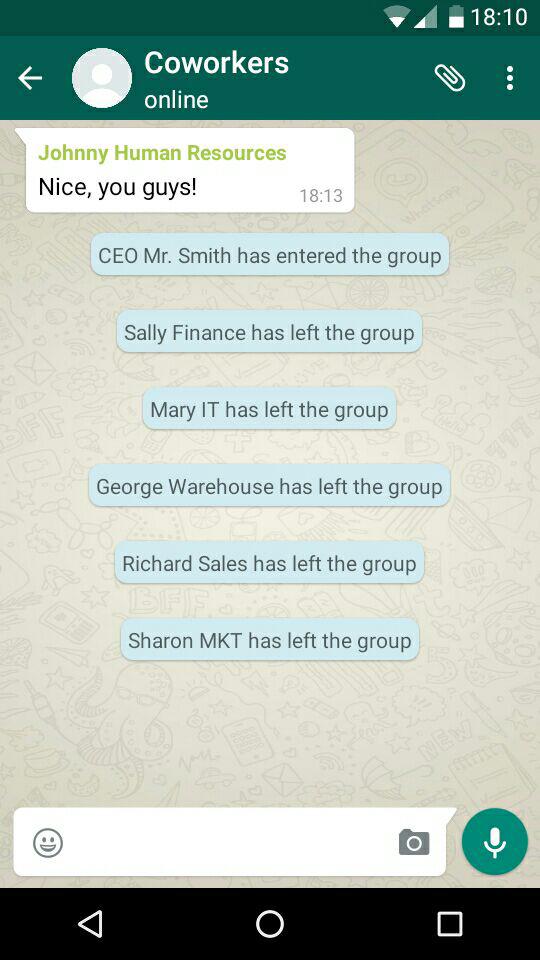

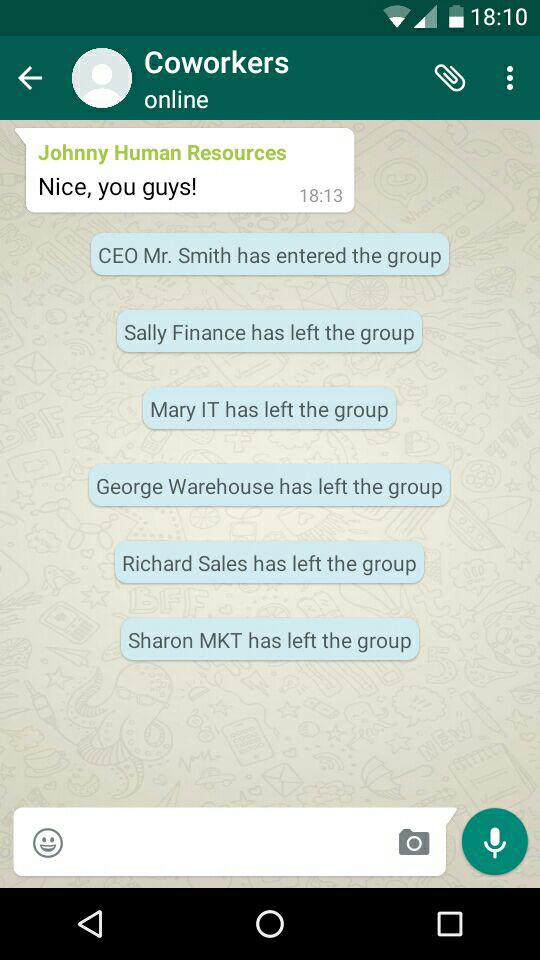

One of the most popular functionalities of instant messaging applications like WhatsApp and Telegram are the discussion groups. Beyond congregating family and close co-workers, the tool also began to be used as a way to enable the organization and sharing of ideas between people that do not necessarily know each other well: fan clubs, neighbors, workers of different departments of the same company or public institution, interested in the same topic.

In a group that gathered owners of houses in a condominium in Distrito Federal, a resident sent criticisms towards the company responsible for its administration. The company got aware of the opinion and decided to criminally sue the resident, arguing that he defamed it in front of “many people”.

Defamation is a crime provisioned in article 139 of the Brazilian Criminal Code, with a penalty of 3 months to a year of detention. For someone to be condemned by defamation, it is necessary to assess if the affirmation was made with the intention to cause discredit in front of others. There are a series of discussions, from the criminal policy standpoint, about the convenience of the existence of a crime to punish these cases; after all, couldn’t this, for example, inhibit the circulation of critical discourses towards powerful figures?

Assessing the case, the judge of the 1st Special Criminal Court of Brasília considered that the resident did not have the intention of defaming the company, but, on the contrary, was only sharing his criticisms and dissatisfactions, in a legitimate exercise of his freedom of speech. It is interesting that the judge placed the discussions in these terms since our researches indicate that the judiciary has been acting with leniency when it comes to requests related to one’s honor and image. Thus, the judge rejected the company’s complaint, ending the process.

The case raises interesting questions for the millions of users of these applications in Brazil. In the first place, what draws the attention is the fact that a company tried to criminally responsibilize a dissatisfied customer. If we think in the variety of sensible topics that are discussed in these groups, like work conditions offered by an employer, the quality of a teacher’s classes, opinions about politicians and public authorities, or even public services like a hospital or a police station, it is worrying to imagine that the manifestation of opinions in these spaces, many times considered by users as relatively private places, can lead the way to a criminal process.

But the issue is not so simple: we also know that it’s in messaging app groups that extremely harmful and illegal contents are being shared, such as images and videos of pedophilia, unconsented intimate images, etc. On the contrary from what happens when these contents are on the web, and therefore hosted in some identifiable server, they are quickly sharable and stored in the devices of all people who are part of the group. And, as hard as it is to restrain the sharing of these contents, users who do it can be liable, as we have observed in our book about revenge porn in Brazil [in Portuguese].

It is evident that such radical transformations in our ways to communicate have impacts in the problems that the law has to face. On one side, it’s also important to think these spaces as discussion environments, in which freedom of speech should be protected, above all in situations like the one in this case, that a company tries to use the criminal path to constrain customers. On the other, it is a challenge to think about manners to reduce the appropriation of these spaces to promote the dissemination of illegal or harmful content. In a moment when the protection of exchanged messages is so discussed, in groups or not, inside these applications through cryptography, it is also necessary to advance the discussion about how to ensure the protection of free expression in face of legislations (and interpretations) that can represent forms of censorship.

Link for the decision in-full [in Portuguese] here.

By Dennys Antonialli, Francisco Brito Cruz and Mariana Valente

Translation: Ana Luiza Araujo